Corrosion is like aging; it does its damage slowly and is easy to overlook—until major systems begin to fail. Unlike aging, we know how to stop corrosion in aircraft. It’s cheap insurance against a slow destruction of your airframe.

The downside is a cleaning up your airplane for at least a few weeks, and possibly several months. You also might discover corrosion damage that would have passed unnoticed for years and now appears as loose rivets and joints. We’re not sure revealing lurking damage is a downside, however. We’d rather stop the spread and know the full extent of any degradation here and now.

This is where owners of fiberglass aircraft get to turn to the next article with a smug expression on their faces. The rest of us who fly aluminum birds should read on.

Aviation Film Stars

Once upon at time, corrosion protection came through a barrier coating sprayed inside the aircraft. They’re still used in large-aircraft operations, but they’ve been long supplanted in GA by fluid thin-film coatings (FTFCs). FTFCs aren’t really barriers. They’re sacrificial dielectric compounds that inhibit electron transfer at the molecular level. They don’t so much block moisture (although they do displace it when applied) as make it unable to promote corrosion.

The two most commonly used FTFCs are ACF-50 from Lear Chemical Research, of Ontario, Canada, who pioneered the product, and CorrosionX by Corrosion Technologies of Garland, Texas. Both products have their following, but CorrosionX seems to have the larger share of the market in the U.S.

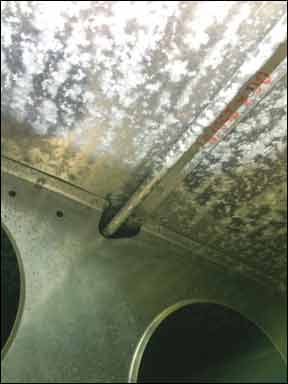

FTFCs are fogged in using high-pressure through slim application wands, which means they can reach nearly every crevice of the aircraft. The compounds are designed to seep into lapped metal surfaces and even around the shanks of rivets. J.D. Hill, V.P. of Marketing for Corrosion Technologies, does a demonstration where he sprays CorrosionX with a dye added on the one side of aluminum sheet riveted together. He’ll count to 60, and the show the dye in a perfect circle around the rivet head on the other side of the aluminum. FTFCs actively seek the micro-spaces between metal.

But as the demo shows, they also weep back out. For a month or so after treatment, it’s normal to see the stuff weeping out of joints and around rivets. It wipes off and won’t harm your paint, rivet integrity or other structure. On the plus side, FTFCs often smoothen cable and control freedom as they act as a lubricant. There are even reports of intermittent microswitches becoming fully operational as corrosion loosens and falls off terminals.

Just to be clear: none of these products will repair corrosion. Lost metal is permanently gone. They will, however, get between the corrosion and the bare metal beneath it often displacing the corrosion so it falls out and off. This can have structural implications (see sidebar on page 10).

When we last looked at FTFC products in 1997, there was some question about methylene chloride and the role of organic fatty acids in promoting fungal growth.

We’ve talked to both companies and reviewed their materials safety data sheets now. The methylene chloride is long gone and both qualify is non-toxic. That’s not to say you should drink the stuff, but it’s safe to wipe off excess with a rag held in your bare hand.

Appliers of both products told us they see about the same amount of this in treated and untreated airplanes (Mushrooms in your fuselage. Who knew?).

Choose Skill, Not Product

CorrosionX is the only commercially available FTFC that meets the new Milspec PRF-81309F, which replaced MIL C-81309E covering these types of products. Military use is about 30 percent of Corrosion Technologies’ business, so the company reformulated to meet the new standard. When they did this, they incorporated several small changes they had waiting in the lab, and the newer CorrosionX performs better on all lab tests than the earlier compound.

J.D. Hill of Corrosion Technologies says this is a reason to seek out CorrosionX. “What you’re buying for yourself is peace of mind and safety margin. Where the price is the same, why wouldn’t you buy the extra margin of safety?”

Mark Pearson, General Manager for Lear Chemical, counters that ACF-50 is a tried and true formulation with 20 years of success in the field. He also points out that customers sometimes buy ACF-50 for the smell. (We’ve heard it described ranging from a sweet, floral smell to brass polish.) These folks told Pearson they detected an unpleasant lingering smell from “Brand X.”

We think all this may be a distinction without a difference in practice. Both CorrosionX and ACF-50 recommend the same reapplication every two years and both show good results in stopping corrosion. Never in our discussions with shops did we hear comments about how owners should stay away from “the other brand.” A shop’s choice to use one or the other seemed to rest much more on what equipment the shop had available—the application gear is different for the two products—and which sales rep the shop owner happen to talk to first.

What’s far more important for your long-term satisfaction than choosing Brand X or Y is getting a shop that has experience in applying FTFCs. “It takes some finesse,” says John Atterholt, director of maintenance for Arizona Air-Craftsman. They’ve been doing ACF-50 treatments for over 14 years. “The first few we did, we laid it in way too heavy. The idea is to get a really good fog without saturating or pooling.” While overapplying the product won’t actually hurt anything, it will make the weeping out much worse and go on for much longer.

We’ve heard some owners complain that they were still wiping up their airplanes over a year later. After talking to application shops, we’re convinced this is due to poor application rather than something intrinsic in using FTFCs. Lear Chemical’s original equipment would pump about a gallon of AFC-50 into a Cessna 172. Current nozzles and techniques treat the entire plane with a quart to a quart and a half.

Both ACF-50 and CorrosionX are harmless to avionics and plastics. In fact, they can be a benefit for exposed electric terminals. But Mike Holoman, whose does CorrosionX treatments for Aviation Tech Services in Edgewater, Florida, points out there are a couple spots to be careful about. Brakes are an obvious friction surface you don’t want a lubricant on, but autopilot friction points are easy for a novice sprayer to overlook.

Holoman runs a mobile treatment service that sprays 45-60 aircraft a year at local FBOs and airports. His recommendation (echoed by several others) was to have the treatment done as the very last step of your annual inspection. “That is when you’ll get the best job. I’ll go though every orifice. You don’t want to pay me to open everything up and then close it back up again.” Atterholt said the same, but added that because of the weeping out, “Just don’t do it before a paint job.”

How Much, How Often?

If you talk to aircraft dealers and shops, you’ll hear that even aircraft in the bone-dry Southwest can turn up with corrosion enough to kill a sale or create a nightmare annual for an owner who didn’t see it coming. Aircraft that live near the coasts like people do, or even carry their owners to such climes regularly, are seriously at risk.

Expect a corrosion treatment for an average piston-single to run $250-350. (Our U.K. contacts quoted £225, which is about $350 as of this writing.) Turboprop singles or light twins can often be had for the same price. Expect to pay around $750 for a mid-size King Air.

The treatment is not permanent. The thin of FTFCs means they spread out to about 3/10,000 of an inch thick. That coating dissipates over time until it’s essentially gone. Applications are generally considered good for two years, but application shops tell us every year in harsh, salt-air climates or for high-exposure operations (such as seaplanes) every year is a better choice. Atterholt says his Arizona-based aircraft regularly go five years before he sees the coating thin enough to warrant a retreatment. So your mileage may vary. There’s no benefit in having extra material or having it applied extra thick. Shops told us it does take a trained eye can see how much of the material is left at annual inspection.

You can also buy small amounts of either CorrosionX or ACF-50 for spot applications or touch-ups. That might be just the thing for the tailcone of a seaplane or what metal parts a composite aircraft does have that warrant protection.

It Really Works

Holoman’s Aviation Tech Services does the corrosion treatments for the Collins Foundation on their B-17, B-24, B-25 and P-51. He told us that before they started treating for corrosion, the Foundation was replacing sheet metal with some frequency. That need has all but vanished. “I’ve never had an airplane owner come back and say it didn’t work in 14 years,” says Holoman.

Pearson of Lear Chemical sums it up well: “For the longest reaching ROI, this is the least expensive maintenance you can do.” Even if that’s not a provable statement, we fully agree that corrosion treatments are we’ll worth the cost and time spent wiping up the lingering mess.