Hail-damaged aircraft are what salvage deals are made of. If you’ve dealt with hail damage as I did with my Grumman after an isolated thunderstorm peppered it on a transient ramp in Wisconsin, you know it can be ugly. Shredded fabric, trashed windshields and gaping holes in the skin are an expensive reality.

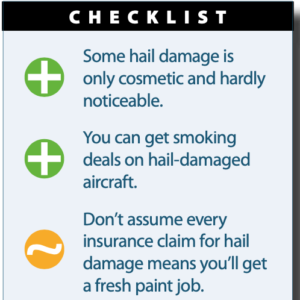

But minor hail damage can be a relatively easy cosmetic fix, even though some owners just take the insurance money and call it a day. That might not be the best idea.

In this article we’ll take a look at hail damage from both technical and economic angles.

COLD HARD FACTS

Hail begins as rain, lifted by updrafts in a thunderstorm. The tops can be as high as 65,000 feet, and temps as cold as a -70 F. As the water droplet is carried upward, it freezes. The bigger the storm, the more the cycle continues until each ice pellet becomes too heavy for the power of the updraft. Mild storms in the summer can create hail of up to ½ inch in diameter.

It’s easy to see why the damage can be severe—a 3-inch hailstone can achieve speeds of 90 MPH with a 120 foot/pound impact. Some hail pellets are round and some are more like clumps of smaller ice balls fused together, which is exactly what they are. No matter the form, the damage is unpredictable.

In flight, small hail can strip paint from the leading edges of wings, the tail and props while larger hail strikes can mean control surface failure. It’s easy to see why.

Designed to be strong where needed, our planes are built as light as possible using the thinnest aluminum sheet (or fabric) that is structurally safe. Aluminum takes it on the chin in a hailstorm. Even big iron with much heavier skins can get beat to death by hail.

My little Yankee was damaged in a five-minute hail storm with ¼-inch hail. It has 0.025-inch metal skins and 0.020-inch skin on the control surfaces. While it was peppered all over and ultimately lost most of its resale value, I decided to leave it alone and continue flying it.

Hail damage is one of the most difficult claims to adjust for insurance companies. Light and medium hail damage are the most common, which tend to be the dime-sized, 1-inch stuff that dimples everything, but generally breaks nothing. This damage absolutely affects the value of the aircraft, but generally does not affect its performance or its structure. When you start seeing holes in the skin, broken light lenses and windshields, then you’ll know a thorough inspection of the structure (and the prop) is in order.

“The most important part of a hail-damage claim is where and when. Telling the adjuster that it happened a while back or out that away, don’t really help your claim,” Gustav Haussler from Master Aircraft Services in Wickenburg, Arizona, said. His shop consistently reels in high marks for customer service, workmanship and overall quality in Aviation Consumer paint shop satisfaction surveys. If you’re faced with hail damage repair, take it someplace that has experience with both painting and structural repairs as they go hand in hand.

BIG-TIME SALVAGE HIT

I spoke to Steve Wentworth at Went-worth Aviation in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a long-established and respected aircraft salvage dealer. Wentworth has bought over 6000 damaged or worn-out aircraft since starting the business in 1986. He told me that one question he asks about every aircraft he bids on is if it has sustained hail damage.

Lots of times an insurance adjustor will respond that the aircraft has a little bit of hail damage, but you can barely see it. This results in an automatic 30 percent decrease of the salvage bid. He asks about the number of dimples and the intensity and depth—factors for further inspection.

“I’ve bought a lot of hail-damaged airplanes over the years, and there are folks who just want a good, solid-flying airplane and don’t care about cosmetic stuff. They can get a pretty good value,” Wentworth said. In fact, Wentworth recently bought his daughter a Piper Cherokee 140 that was hail damaged. She got a solid, low-time airplane with great radios for half the price of what a non-damaged plane would cost.

Terry Riney owns the Terry Riney aircraft insurance agency in Pine-hurst, North Carolina. The company is a broker for all aircraft insurance companies (less Avemco). Hail claims are somewhat rare to him, but they do happen and when they do, he has to take it as it goes. Of course, Terry isn’t based in the Midwest, so he may not see claims with severe hail damage. Still, hail happens anywhere.

As a broker, Riney doesn’t have much to do with the assessment of the damage or any repairs. He told me that many owners will negotiate a sum based on the cosmetics, but never fix the aircraft. That it performs the same—and the owner has a wad of cash in hand—is all that seems to matter to some. Others want the aircraft either fixed or totaled. See the sidebar on page 17 for more on insurance claims.

Depending on the hull value, it isn’t difficult to total out a small aircraft. But with bigger machines, the issue could be different. Riney recently dealt with a Beechjet with $69,000 in leading-edge damage from flying through hail, but it’s a million dollar-plus aircraft, which puts the relatively small repair cost into perspective.

I asked Riney if owners accept payment and then move to another insurance company and insure at higher, undamaged hull value—either trying to claim new damage or trying to sell the plane for an undamaged value. He has seen little if any of this. While there might not be questions regarding hail damage (specifically) on an insurance application, there is a section on existing damage. Many owners forget that there is hail damage because it may be small in terms of overall cosmetics. Plus, they have been flying the plane in this condition for a while with no issues. But that doesn’t mean it will go unnoticed forever.

“Hail damage is much more important to a buyer than a seller,” Riney rightfully said. Anyone can get stuck with one that’s taken a hit. He actually owned a Cessna 182 for a while before he even noticed that it had slight hail damage.

Hail damage is usually covered in a policy, and companies will repair (but not rebuild) an airplane if the hull value warrants it, and the owner doesn’t opt for a payout. Riney and others compare hail damage to the condition of logbooks when it comes to establishing aircraft value. He recommends that a buyer physically check any reported hail damage and negotiate a price they can live with. If you buy the plane right, this “relative” value will follow the airplane the rest of its life, and then the next owner can buy it right, too, putting off the repair until the next paint project.

FIXING THE DENTS

Repairing hail damage can be rather time-consuming and run the gamut from slight surface filling and paint work to completely reskinning the top surfaces. It is reasonably easy to replace the upper skins on wings and control surfaces, but extremely time- consuming. Not all shops are up to the task—it requires a certain skill level and knowledge of structural repairs, especially for composite aircraft.

Darrell Yelton of Cirrus Aircraft said that Cirrus models (like many other composite models) are relatively easy to repair unless there are penetrations. Drill a pinhole and inject a proprietary Cirrus resin until the void created by crushed foam (the skins are a sandwich, with about a half-inch of foam between two layers of fiberglass) is filled and it begins to ooze out of the hole. Then, sand, paint and fly.

Of course, major structural repairs to composite aircraft might require the assistance of the OEM. See the article in the April 2020 issue of Aviation Consumer for more on dealing with general composite repairs.

Aluminum airplanes aren’t so simple. There is a bit of rebound with aluminum, but it easily bends when impacted. Kent White (“The Tin Man”), who does phenomenal metal forming work, calls this metal flow. Metal is moved forming a shape, and in the case of hail damage, the metal is stretched from the center of the impact point. The metal completely surrounding this impact point is stretched to create the difference in surface area of the metal. The only way to eliminate this dimple is to fill it or pull (compress) the metal back to its original shape.

This can be done using different techniques. On airplanes, you don’t drill a hole, insert a screw and pull the dent out. There has been some luck using the paintless dent removal technique, and a couple of national automotive paintless dent repair companies (like The Dent Guys and EZ Dent) have dipped into the airplane business, working under the supervision of IA mechanics. It’s a tough process on aircraft because of the lack of room between the upper and lower skins of the wing, as one example. Another problem is that unless they are trained, body shop techs might not understand the alloys used, the temper of the aluminum and the techniques needed to safely work the metal.

The useful tool that applies small fixtures to the dent with hot-melt glue can be handy and does not affect the paint finish. Technicians use a light bar behind the work to check for variations in the surface and pull slightly until the dimple is removed. On thin-skinned surfaces, this puller needs to be supported to keep from making new impressions. You can see this process done on vehicles with a YouTube search. Long rods with special ends are also used, but require a pivot point where the rod is braced to push slightly from the inside out.

There are also technicians who use a powerful magnet on the outside and a steel ball that rolls around inside the skin, sort of like an internal English wheel, with a minimum surface of the ball putting pressure on the dent “peak.”

Another way to pull out a dimple is the application of dry ice. This technique has seen different degrees of success and is time-consuming because you have to apply the ice, check, reapply, recheck, ad infinitum. The theory of heat expanding and cold contracting has created a number of variations on this. I have heard of success on very thin-skinned control surfaces, but on thicker material the dent could reappear after the temperatures stabilize. Some shops have reported good luck by using dry ice along with suction (and even a shop vac) to pull out a dent.

Filling a hail dimple is difficult and time-consuming. Bondo (the featherlight aviation version) takes time and a lot of sanding. Some techs have gone to resin-filled aluminum paste. Both of these have to be applied sparingly and in a number of applications. I know from experience. Too much and you will never get it to sand flat. There are now self-etching filler materials that will stick we’ll to aluminum. There are also newly available primers that build up and self-etch. I wonder how this would work on the smallest dings.

THE BOEING WAY

If you have a valuable warbird or rare classic that’s been hit by hail, there’s an expensive electronic dent removal (EDR for short) solution from Boeing. It says the process relies on the fact that the magnetic permeability in metals is much lower than in air. In other words, it takes longer for a magnetic field to penetrate through a metal than it does in air.

When the EDR unit’s coil is placed over the damaged area, the capacitors in it release 36,000 amps of electric current in 1.5 milliseconds to produce a magnetic field on both sides of the dent. A second set of capacitors then collapses the nearest magnetic field by instantly discharging half the energy generated by the first set of capacitors.

Because of the low permeability of the metal being repaired, the magnetic field behind the dent is kept relatively constant. This imbalance is what pushes the dented metal outward toward the face of the EDR coil.

This was recently used to remove dents from a Boeing B-17. If your aircraft is valuable enough, it may be worth it.

Since hail damage will often involve your insurance company, it’s best to learn how your particular insurer will handle a hail-damage claim when you buy or renew the policy. Don’t always assume there is complete coverage to your liking. Since aircraft insurance policies vary widely from company to company (especially now in a hardened market), ask your broker for advice. They’ll have specific experience with these kinds of claims—which could be considered cosmetic. We’ve heard of some companies limiting cosmetic damage to 10 percent of the insured value.

We asked Marci Veronie at Avemco specifically how the company handles a typical hail-damage claim. First, Avemco assumes you have purchased hull coverage, paid the premium and complied with all of the terms and conditions of the policy. Veronie acknowledged that some hail damage is extensive enough that the cost to repair it is such that the aircraft becomes a constructive loss.

“In this case, you would receive payment for the insured value of the aircraft and Avemco would retain the salvage,” Veronie told us about damage that results in a total loss. If the damage is not severe enough to total the aircraft, Avemco will pay to repair the aircraft back to the condition it was prior to the loss. In other words, and this is important, if the aircraft’s paint was in ratty condition before the hail damage (or if the aircraft hasn’t been painted yet—as in the case of some homebuilts), Avemco won’t be paying for a new paint job.

Veronie reiterated that in some cases, the hail damage is cosmetic in nature and doesn’t affect the airworthiness of the aircraft. Since some owners may not want to put the aircraft in the shop for a repair, Avemco would offer a monetary settlement, while reducing the value of the hull by the claim payout amount until it was repaired.

“This prevents us paying for the hail damage a second time in the event of another loss,” Veronie said.

—Larry Anglisano

FINAL ANALYSIS

Unless it’s structural in nature, repairing hail damage is a value judgment by the owner. Best case, you can control whether or not you can live with cosmetic flaws. Every person has a price, they say. You can actually rush to judgment with hail as there are many reports of smaller hail dimples disappearing over time as the aircraft sits outside in the heat.

If you store the aircraft outside, you’ll want hull insurance, and avoid over- or undervaluing the value of the plane. Overvaluing the hull will boost the premiums and undervaluing could send it to a salvage yard.

Should you get a check and want to repair the damage, take it to the right shop. I would bet that any good aircraft metal shop based in or around the “hail alley” states would have a leg up on shops that seldom see hail. Your IA might be inclined to work with a local dent shop, but they might need hand-holding while working around airplanes.

Last, some of us are so cheap we’d take the check, buy a paintless dent kit and spend a million hours pulling out the little puckers. But hey, it gets us out of the house for a little bonding with the aircraft.