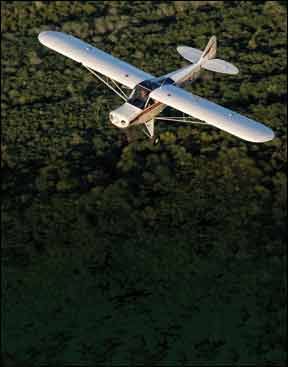

Other than having wings, an engine and a tall sticker price, certified and light sport airplanes don’t have much in common save one thing: People who buy both will pay for higher performance. And that’s the idea behind the new Lycoming O-233-powered Super Legend.

After a fashion, the Super Legend is to the standard Legend as the Super Cub is to a J-3. The Super Legend is based on Piper’s venerable PA-18 and, according to Legend’s Darin Hart, some of the parts are directly interchangeable. (That’s true of the O-200 Legend, too.)

With the Super Legend, American Legend is going after that strata of the market to whom performance, features and cache matter more than price. That turns out to be the dominant share of buyers, according to LSA market summaries. When we visited Legend’s Sulphur Springs, Texas factory in late August, it was in the final stages of LSA approval for the Super Legend. Hart told us despite the higher price tag, every other buyer is opting for the Lycoming version over the Continental O-200 model. In this report, we’ll take a look at how the O-233 (and flaps) transforms the Legend airframe.

Like A Cub, But Different

Although sales have been tanked by the downturn, Legend Aircraft has established itself as one of the most successful LSA manufacturers, with about 200 aircraft in the field. The appeal of the airplanes—rag-and-tube construction, tailwheel, sticks and heel brakes—is timeless and not just for those full-circle pilots who learned to fly in Cubs half a century ago and who can afford to get back to their roots with a new airplane. The Cub mystique transcends generational boundaries and Legend has found some buyers among younger pilots, plus some flight schools.

The airplane and the company springs from Darin Hart’s interest in seeking a kit Cub for his own use in 2004. When he and future partner Tim Elliott scoured Oshkosh and couldn’t find anyone who could deliver a Cub kit in under 18 months, they decided to build their own, direct from Piper’s original drawings. Two airplanes led to more ideas, the LSA rule emerged and Legend Aircraft was the result.

The Super Legend is an iteration of the original Legend Cub which is itself based on the Piper Super Cub. The fuselage is three inches wider and instead of one clamshell cabin door on the right, there are two. But the Legend is otherwise nearly a Super Cub clone. The Super Legend is yet closer. At the company’s factory, Hart gave us a spinner-to-tail tour of the new airplane.

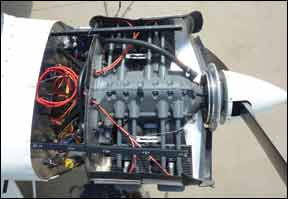

The most obvious change is the engine. Lycoming announced the O-233 in 2008, but its developmental pace has been more simmer than rolling boil. Only a handful of manufacturers are offering it and Legend is one of the first. The O-233 is essentially a shaved-down O-235 with the addition of a simplified electronic ignition system in place of heavier mags. It has cylinders with reduced cooling fins to save weight and a redesigned accessory case, the result of having to accommodate just a single permanent-magnet alternator for the ignition system rather than two magnetos. As we reported in the February 2012 issue of Aviation Consumer, Precision Airmotive developed a fuel injection system—essentially a downsized Bendix RSA constant flow design—but the Super Legend has a conventional updraft carburetor rather than injection. Hart thinks the injection system would add complexity—and perhaps weight—for no benefit and a potential downside for floatplane ops where quick starts for a short burst of power for docking and water taxi are essential.

As it is, the O-233, at about 209 pounds in the Super Legend, gives away 10 pounds to the O-200 and as much 35 or more to the much lighter Rotax 912 series. At 115 HP, the O-233 has a power density of .55 HP per pound compared to .5 for the O-200. The Super Legend we flew had a new, 76-inch carbon fiber ground-adjustable prop from Sensenich, which felt like it had more bite than the 72-inch prop on the Legend. But the feel could have been due to both the additional power and the prop.

New Engine Mount

The O-233 is hung on a centerline-thrust mount which Hart says is a favorite among owners in Alaska. To improve visibility over the nose, the Super Cub’s mount is offset 4 degrees downward, but the Super Legend’s is on the longitudinal centerline. This improves performance slightly because less elevator trim moment—and less drag—is required to keep the nose in level flight. It also means that the Super Legend’s nose cowling is a few inches higher than it would otherwise be, but in our view, this doesn’t hinder-taxi visibility. The Super Legend will eventually be offered as both an amateur-built or E-LSA kit. In the former, a builder could opt for up to 180 HP, says Hart, because the airframe is engineered to accommodate the power. It could also be flown at a maximum weight of 1650 pounds. The airplane we flew had an empty weight of 862 pounds for a useful load of 460 pounds. With two people aboard, that allows for 20 gallons of fuel against the Super Legend’s total capacity of 30 gallons usable in two wing tanks. Legend is looking for another 15 pounds of weight in order to accommodate amphibious floats on an empty weight of 995 pounds. One easy place to find that would be to replace the lead-acid starting battery with a lithium-ion battery. (See the sidebar for more.)

Elsewhere on the airplane, Legend has trimmed weight at every turn. The two side doors are carbon fiber as are the floorboards and the engine cowl components. In place of composite or traditional upholstery, the sidewalls are made of sail cloth and simply snapped into place. We also noted that the flap hinge mounts are drilled with lightening holes.

Aft of the rear seats is perhaps the most noticeable change in the airplane, other than the engine. The Super Legend has a greenhouse over the baggage area and a fold-forward rear seat. “That’s another Alaska favorite,” Hart said. “You can look back and see the tail, you can see what’s behind you and what’s above you.” It also sheds plenty of light into the baggage compartment and into a turtledeck storage area suitable for skis, rifles or fishing poles accessible through a snap-on fabric cover. For now, the baggage compartment—which has a hinged outside door—has a 50-pound limit. But Hart says once final weight-and-balance calcs are done, capacity will increase to 100 pounds, if not a bit more.

Further aft, the Super Legend sports a tail design identical to the Super Cub, meaning it has an aerodynamic elevator whose tip leading edges extend ahead of the hinge line. Overall, the horizontal stabilizer/elevator provides about 18 percent more surface area than the Legend Cub has. This is noticeable in flight.

The Super Legend has some interior changes, too, including a redesigned instrument panel and a novel bungee seat that we found comfortable. The new panel has higher lower edges on each side of the center, yielding more knee room for tall pilots. It’s also tilted back slightly to improve viewability of the avionics. Speaking of which, as with most LSAs, you can spec about what you want for electronics in the Super Legend. The choices include Garmin’s aera line, the GPSmap 696 or a Dynon Skyview. The demo airplane we flew had the 696, plus a JPI EDM-730, an all-in-one engine monitor that graphically displays engine temperatures and pressures, OAT, carb temperature and fuel flow, among other data. In short, in a small, colorful package, it displays engine data usually found only in full-up EFIS systems and certainly not something you’d expect to find in a Cub.

While the Legend is soloable from either seat, the Super Legend is front-seat solo only. That’s not due to weight-and-balance, but because the fuel selector and ignition switch can’t be reached from the rear seat. While the rear seat folds forward for long cargo, the front seat can be adjusted fore and aft via a rail-and-pin arrangement, another upgrade over the standard Legend. Heel brakes remain standard, toe brakes are optional.

Flying It

The O-233 doesn’t have a primer, but the carburetor has an accelerator pump and one shot on the throttle richens the intake enough for an easy start. We did a couple of hot starts and found them effortless, probably due to the electronic ignition’s more energetic spark. But the system does have one quirk: Its default power source is the ship’s bus or battery. If that fails, the engine’s own PMA takes over to power the ignition system. However, if engine RPM drops below 800, the PMA lacks the output to power the ignition modules and the engine will quit. While that scenario is unlikely, we still see it as undesirable.

Ground handling in the Super Legend requires a touch. From the front seat, the slightest neck crane will deliver good visibility over the nose, so S-turns aren’t really necessary. If they’re used, however, they should be shallow because if you don’t anticipate stopping the turn with opposite rudder, the Super Legend tends to go its own way whether you like it or not. The best technique seems to be to worry the turn reversal with a touch on the heel brake.

With 15 additional horsepower over the standard Legend, we didn’t expect a noticeable performance bump from the Super Legend, but we might have sold it a little short, at least for takeoff and climb. We’re not sure if the larger prop was responsible, but the Super Legend has a brisk takeoff roll and requires a surprising stab on the right rudder to keep it tracking straight once the tail comes up.

It will happily climb about 900 FPM at 50 MPH indicated right after takeoff and then settle into 700 FPM at 60 MPH, which is close to best rate. The higher speed yields a better view over the nose, but at either speed, the EDM 730 indicated no hot cylinders during climb.

Handling is not quite like the Legend. With the larger tail feathers, the Super Legend has solider pitch feel and probably has a higher pitch rate, although we didn’t measure it. It definitely requires less fussing with the trim. A couple of turns on the window crank occasionally does it. This was most noticeable in flying takeoffs and landings; the pitch force excursions aren’t great enough to require much retrimming. Cruise speeds are about 100 MPH true between 4000 and 5000 feet on a fuel flow of 5.1 GPH, using the JPI’s lean find function.

We weren’t quite prepared for how slow the Super Legend will fly before stalling. The ASI touched about 20 MPH indicated just as the buffet appeared, but Hart said the tail actually stalls before the wing. The airplane retains mushy roll control with ailerons through the buffet with no tendency to fall off on one wing. Like other LSAs we’ve flown, the Super Legend has a benign parachute mode.

There’s a perceptible pitch change when the flaps are deployed via a manual lever above the pilot’s shoulder, but not much trim change. Getting the 18-degree flap notch is easy, but because the lever is located too far aft, cranking it to 45 degrees is almost painful. Hart says he’s planning a flap handle redesign that will fix that. Landings in the Super Legend were somewhat of a revelation. The original Legend isn’t exactly slick, but without flaps, it takes effort to get it comfortably slowed down. That means a bounce—if not several bounces—until you get the range dialed in. Not in the Super Legend. With full flaps, the default speed is 50 MPH indicated unless you aggressively trim it faster. We were comfortable crossing the fence on a grass runway at 45 MPH indicated and touching down with so little residual energy that landings were satisfyingly agita free.

With a little careful braking, they can also be impressively short.

Hart told us he has talked to Piper about bringing back the Super Cub under some sort of license arrangement. We can see the sense of that.

Although the Super Legend’s useful load is limited by arbitrary LSA rules, it’s structurally capable of carrying 330 additional pounds—nearly two people. It’s apparent why the Super Cub has endured as a popular utility airplane, despite its small size.

The Super Legend’s base price is $146,800, but the typical invoice would likely be $160,000 to $170,000, compared to about $140,000 for a Continental-powered Legend. The LSA market remains anemic at best, but we’ve learned that if there’s any sweet spot to it, it’s at the higher end of the price spectrum. Cirrus learned that with the SR22 and American Legend aims to repeat the trick with the Super Legend. In our view, the airplane probably has the stuff to pull it off.

For more, contact American Legend at www.legend.aero or 903-885-7000.