It’s not surprising that Decathlons and Citabrias rank high on the list of fun airplanes to own, and it’s not uncommon for them to be second or third airplanes parked next to the family traveler. That also means these two-place aerobats can be easy to own.

And if you have a burning desire to add an aerobat to the fleet, a Decathlon or Citabria might be a much better bet than something like a Pitts or Extra. Owners and our own maintenance experience tell us that with the right preventive care (and storage), they’re relatively trouble-free and we’ll supported.

Like anything else, the used market has some gems and ones to run away from. Here’s a fresh look.

MODEL HISTORY

The Citabria is based on the Champion 7-series airframe. The similar, although more rugged, 8 series is used for the Scout bushplane and the more fully aerobatic Decathlon.

And since some Citabrias are indeed old airplanes, there are a few things to watch for when looking for one to bring home, most notably the wooden wing spars found in pre-1990s models. There’s also the possibility of strut corrosion, similar to what Piper and Taylorcraft owners have been finding for some years.

As we reported in the September 2017 Aviation Consumer, American Champion can retrofit new, all-metal wings onto older airplanes for owners who prefer them. Plus, many Citabrias have undergone the upgrade and those are the ones you want, in our estimation, because they also bring a gross weight increase.

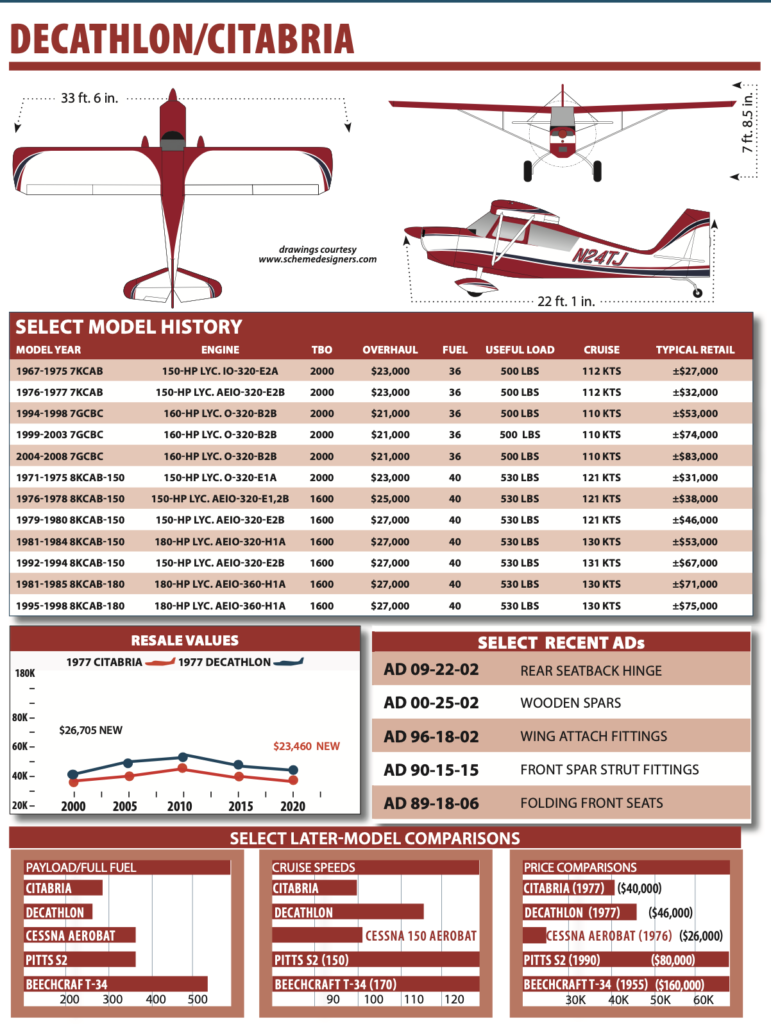

The Citabria traces its roots back to the Aeronca Champion, although you likely know it as the Champ. It’s one of several postwar tailwheel trainers that included the Piper Cub, Cessna 120 and Luscombe. The postwar production boom resulted in tens of thousands of these airplanes, but by 1951 the market was saturated and production ended. The 7EC Champ was returned to production periodically and ended up being manufactured as an LSA by American Champion as the Champ, with a 100-HP Continental O-200 engine. Worth mentioning is it became the only light sport entry that’s also fully certified. In 1959, the first airplanes that would eventually become Citabrias appeared, dubbed 7GC. In the years that followed, a fistful of airplanes debuted, each called Citabria. And man, was it confusing to keep straight because eventually there were six variants. In some cases, the differences between models are minor, in others more significant. Here’s a rundown:

• 7GC—Produced only in the 1959 model year, it had flaps and a 140-HP Lycoming O-290.

• 7GCB—Essentially the same as the 7GC, but with a 150-HP Lycoming O-320; produced from 1960 to 1964.

• 7GCAA—Aerobatic, with the same Lycoming as the 7GCB. No flaps. Introduced in 1966 and in production today as the 7GCAA Citabria Adventure.

• 7GCBC—Aerobatic, same as the 7GCAA, but with slightly longer wings and flaps (introduced in 1967) and in production as the 7GCBC Citabria Explorer.

• 7KCAB—Introduced in 1966 as a more capable aerobatic ship, with a fuel-injected 150-HP Lycoming and inverted fuel and oil systems. It was produced through the 1977 model.

• 7ECA— Introduced in 1964 as an aerobatic follow-on to the Champ. Originally, it had a 100-HP Continental O-200, soon replaced by the 115-HP Lycoming O-235. It is in production as the 7ECA Citabria Aurora.

The 8KCAB-150 and -180 appeared in 1971 and 1977, respectively, and sported both more power and constant speed props, which are nice for combination aerobat/cruisers.

Most of these airplanes were built by Bellanca, which went belly up in 1980 at the beginning of the GA slump. A brief attempt was made to revive the line in 1984, but the timing wasn’t right and production stopped again. American Champion acquired the type certificate in 1988 and started production in 1990.

In 1990, American Champion started delivering Decathlons, followed by the Scout in 1993. 1994 saw the reintroduction of the 7GCBC Citabria, followed by the 7ECA in 1996 and most recently the 7GCAA.

The 7GCBC model has proven the most popular, followed by the 7KCAB. The total production numbers aside, currently the 8KCAB is the most popular, followed by the 8GCBC. The latter, built as a low-end aerobatic airplane capable of inverted flight, didn’t make it largely due to competition from the Decathlon. The Decathlon, with its shorter wings and semi-symmetrical airfoil, was a better buy for aerobatics, though the 7KCAB is still a fine airplane.

Today’s Citabrias are essentially the same airplanes introduced decades ago (although American Champion offers engines with up to 210 HP), with one significant difference: the wing structure. The Bellanca airplanes had wooden wing spars, which sometimes suffered cracks and were the subject of ADs.

American Champion came up with an all-metal structure and incorporated it into all new aircraft. Owners of earlier models can also have the new wings retrofitted. The cost is steep at (depending on model) $20,900 to $27,000 per set, plus additional costs for installation and for fabric and paint finishing, but the new wings boost the gross weight, are free of repetitive inspection requirements and surely increase the resale value of the airplane.

The factory can also supply new, improved front struts and aileron spades. All of these are worthwhile improvements to older aircraft. When shopping for a Citabria, extra consideration should be given to upgraded models.

There are a variety of Citabria and Decathlon models in the current lineup (with several engine choices), including the flagship Xtreme Decathlon. This has a redesigned cowling to accommodate a 210-HP Lycoming AEIO-390-A1B6. The Xtreme Decathlon also has a 30 percent increase in roll rate, without altering its ground manners. It also has a longer landing gear and a wide-chord MT propeller. You’ll pay top dollar for one—well north of $200,000, and most have low time. That’s also the case with most late-model Decathlons. The Fall 2020 Aircraft Bluebook prices a 2018 Super Decathlon at around $245,000.

FLYING THEM

One of the things that make these airplanes so desirable is their ground handling, which isn’t always the case with a light taildragger. The Decathlon and Citabria models can be easy to transition to, although easy is a relative term. If you have little or no tailwheel experience, you have to respect the fundamental differences between conventional and tri-gear airplanes. On the ground, tailwheel machines are more prone to swapping ends due to the location of the center of gravity aft of the main landing gear. Yes, it can get sporty.

This means staying alert to side loading of the landing gear. Staying on the centerline and being unfailingly in command of the rudder are keys to success. It also means that the ailerons must be properly positioned for the wind when on the ground. If you fail to do that, you can wind up in a ditch, or worse, during the landing rollout or even while taxiing.

But get these airplanes airborne and they are forgiving in virtually all flight modes, although these are definitely rudder airplanes, requiring work to keep the ball centered due to adverse yaw. The elevators and rudder are nicely harmonized, while the ailerons are comparatively heavy and less effective. Adding spades corrects this characteristic and we think they are worth the investment.

Stalls are mild, giving aerodynamic warning whether flaps are up or down, and stall speeds are as low as about 40 knots for the flap-equipped 7GCBC. Citabrias and Decathlons will spin nicely if the ball is not near the center at the stall. Spin recovery is positive, but requires several hundred feet, even if initiated immediately. Although stressed and certificated for loops and rolls, the Citabria is not a serious competition-level machine, although the wreck reports prove that some pilots believe otherwise. It’s ideal for initial acro training and hours and hours of fun, but only the 7KCAB (and Xtreme) have an inverted fuel and oil system. The other variants are generally limited to positive-G or G-neutral maneuvers such as inside loops, barrel rolls and the like—still not a bad way to sharpen skills.

As with many light airplanes one potential handling trouble spot is PIO (pilot-induced oscillation) during landings. Although not unique to Citabrias, the spring-steel main gear can bounce the airplane if the pilot drops it in too hard or fails to go around. More bounces, a groundloop and/or nose-over and/or prop strike are realities.

To avoid a rotten day, touchdown for a wheel landing should be as close to zero-rate as possible and for three-pointers, as close to the stall as possible, with the stick back. Land too fast and you’ll bounce once or twice or more. Welcome to the world of taildraggers.

DECENT PERFORMERS

But not blistering fast, so don’t plan on getting anywhere in a hurry.

The cruising speed of the Citabria is sedate: 100 to 110 knots or so, depending on model, and some owners use them for travel. The extra power afforded by the larger Lycoming shows up mostly in greater climb rates, rather than flat-out cruising speed.

The longer wings of the 7GCBC help and according to Champion, the 7ECA climbs at 740 FPM, while the 7GCAA moves up at 1167 FPM and the 7GCBC climbs at 1130 FPM. We can attest that the Decathlons cruise faster.

Takeoff and landing performance are impressive, particularly for the wood-spar 7GCBC. According to our sources, takeoff ground roll is only 296 feet, and a 50-foot obstacle can be cleared in 457 feet, although those numbers might be a touch optimistic. Landing distance over a 50-foot obstacle is also in the 900-foot range, with about a 500-foot ground roll.

LOADING, ERGONOMICS

As we noted, an important thing to remember about the new metal wing structure is that it gives the 7GCBC Citabria a gross weight of 1800 pounds, compared to 1650 for the older models. That’s nothing to sneeze at. Gross for the 7GCAA and 7ECA was upped in early 2001 to 1750 pounds for metal-spar versions. The Citabrias, especially early versions, are not known for their load-carrying capacity. While the lifting ability varies according to model and equipment, in general, it’s not possible to fill the seats and tanks at the same time.

Keep in mind that when two large people wearing parachutes consider aerobatics, they may be approaching gross weight even before fuel is added. Still, owners report that staying within the CG envelope is not a problem.

As for ergos, the cockpit and panel controls are laid out so that everything falls easily to hand. You fly solo from the front seat and visibility is fair in flight. In the three-point attitude, the nose doesn’t block forward visibility. The front stick length gives just the right leverage for the control gearing, especially with aileron spades. The rear stick is short and instructors report that it often takes both hands to get full aileron deflection in a roll in a non-spade aircraft. Each throttle (one for each seat) is where one reaches almost unconsciously with the left hand; the carb heat knob is immediately below.

Most Citabrias have toe brakes, although some of the earliest have that bane of many a pilot’s existence—heel brakes. Front seat travel is limited and short pilots may have difficulty getting full rudder throw without using an extra back cushion. Citabrias and Decathlons are some of the better airplanes for tall pilots—the high roofline means not having to bend over to look out the side windows. The seats are surprisingly comfortable and the cushions snap out quickly when it’s time for parachutes. The panel is low and slender, making installation of more than basic VFR instruments and radios challenging. Headsets or ear plugs are a must as the cockpit noise level is about on par with the proverbial boiler factory.

The fuel system is utter simplicity, with three sump drains, one direct-reading mechanical gauge in each wing root and a simple fuel selector. Fuel supply is by gravity feed, of course, but as with all Lycomings, there’s also a boost pump.

MAINENANCE, SUPPORT

There’s nothing particularly complicated about maintaining these airplanes, but just the same it pays to seek out a mechanic who’s familiar with tube-and-fabric airplanes and, if looking at an airplane with the older wing, who has experience with wood. The covering is Dacron, which is durable, although not good forever. Most owners suggest keeping the airplane out of the sun and we concur. Owners and mechanics familiar with the type tell us that aside from making certain the ADs are complied with, especially AD 2000-25-02 R1 on wooden spar airplanes, a serious look at all of the fuselage tubes, especially those aft and low, for corrosion and proper inspection of the wooden spars, there are no particular trouble spots to watch for when shopping for a used Citabria. Early model wing struts had thinner, 0.035-inch wall thickness as compared to the more recent 0.049-inch wall thickness. AD 77-22-5 called for replacement of the old struts, and most if not all airframes should have the heavier struts installed; the presence of a placard limiting speed to 153 MPH is proof of the thinner struts.

Also watch for cracked seatbacks. There have been accidents in which the pilot’s seatback failed, planting his torso on the aft stick with disastrous results. The landing gear U-bolts can develop cracks, especially in airplanes subjected to rough fields or training.

Like most taildraggers, it’s difficult to find a Citabria that has not been groundlooped at some time in its life, simply because they are tailwheel airplanes. A groundloop by itself is not cause for alarm; the trouble arises when the loss of control results in a wingtip and/or prop blade hitting the ground or the landing gear being damaged. Wing damage repair is not always recorded in the logbooks, so inspect any Citabria for wing repairs, especially, as the experts tell us, because most wood spar compression cracks can be traced to an impact event, usually from a groundloop. A full set of service bulletins should be a part of any owner’s library, since they can point out areas of weakness.

The new wing structure was developed as the result of cracks in Decathlon wing spars, not those of the Citabrias, so the presence of wood is not necessarily a deal-killer. Nevertheless, years of movement of aluminum ribs against a wood spar means we’d look carefully before buying a wood-spar Citabria.

Newbs can get sloppy and blast right through redline airspeed, so a buyer should assume that an airplane capable of aerobatics has been doing them and that pilots have made mistakes in the process, so inspect the wing and tail carefully.

Fortunately, the Citabria’s systems are simple and inexpensive to maintain, so previous owners are more likely to have kept things up to snuff than owners of more complex, expensive and labor-intensive hangar queens. Avoid ones that have been neglected. There are plenty of resources along the way.

First and foremost, of course, is American Champion. They’re located in Rochester, Wisconsin (262-534-6315), and www.americanchampionaircraft.com. We like the fact that the factory puts a number of its service bulletins and technical information on its website as a free service.

Another source is in Santa Paula, California, home of CP Aviation (www.cpaviation.com) that specializes in the line. CP Aviation also offers aerobatic training in Citabrias and Decathlons.

For owner support, it appears the Citabria Owner’s Group has disappeared, but there’s a Bellanca-Champion Club based in Coxsackie, New York, with a website at www.bellanca-championclub.com. The site has training, operating and parts manuals for sale, plus it has a member forum.

We have long used the Citabria line as a shining example of good tailwheel handling. Nevertheless, because the aircraft’s center of gravity lives aft of the main landing gear, they are not tolerant of an inattentive pilot on landing or takeoff.

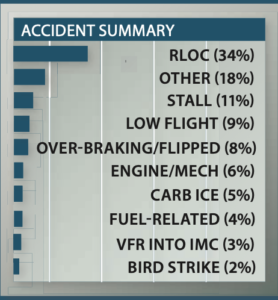

This was confirmed by our review of the 100 most recent Citabria accidents. Thirty-four percent involved runway loss of control—all but a few on landing. Eight Citabrias flipped over due to overly enthusiastic braking (on landing or rejected takeoff) or picking the wrong surface on which to alight. Accordingly, two out of every five Citabria accidents involved loss of control while the wheels were in contact with the ground—something we think deserves respect on the part of a pilot considering a purchase.

Looking more closely at the RLOC issue, the overall numbers are slightly above what we expect to see for a tailwheel airplane. However, about a quarter of the accidents involved training. Because the Citabria is a popular tailwheel trainer, we aren’t waving any red flags over its ground handling from the raw accident numbers alone. For example, the Cessna 190/195 series has a RLOC accident rate in excess of 50 percent, and it’s rarely used for training. By comparison, the Super Cub has an RLOC rate of 40 percent.

We also note that the Citabria has a much lower rate of accidents involving a nose-over due to over-braking or runway surface than its peers, the Super Cub and Aviat Husky. We attribute that to landing gear geometry.

We stick with our opinion that the Citabria line has some of the best ground handling in the tailwheel world, but note that all bets are off for a pilot who does not respect the demands of tailwheel operations and/or insists on flying final any faster than 60 KIAS. Extra speed on landing is not a Citabria pilot’s friend.

We were pleased to see a very low rate of engine power loss accidents. There were only six, although three were unexplained as they could not be duplicated afterward. There were five carburettor ice forced landings. Pilots seem to think that Lycoming engines are immune to carb ice—they aren’t.

There were only four fuel-related accidents, a tribute to the simple “on/off” fuel system.

Citabria stall behavior is docile, so we were a little surprised to see 11 stall-related accidents until we noted that more than a third came about when the pilot was flying low and maneuvering aggressively, including doing low-level aerobatics.

Fun to fly airplanes seem to be directly connected to crashing while flying low—often due to hitting power lines. Even a great airplane design can’t cope with assertively poor judgment. Sadly, two pilots hung cameras on their Citabrias to record their low-level flying. Their heirs got to see the videos. One pilot used his Citabria to assist with a cattle drive. He made four passes before hitting power lines and crashing.

A pilot who drifted left off of the runway during takeoff kept going—and drifting left—until he smacked into a hangar. He couldn’t understand losing control—it had only been seven years since his last flight review.

OWNER COMMENTS

I have owned several taildraggers including a Super Cub. From an all-around perspective, you just can’t beat a Citabria. My first was a 1997 model with a 160-HP engine and my current airplane is a 2011 model with the same powerplant.

Citabrias are more comfortable than Cub-iteration aircraft. They provide more head and shoulder room and allow you to sit in the airplane, rather than wear it. Citabrias won’t take off quite as short as a Cub, but they are faster. My Super Cub with 31-inch tires would cruise less than 100 MPH, while the Citabria with 26-inch tires topped out about 125. A 25-MPH difference may not seem earth shattering, but on round trips over 1000 miles, it makes a huge difference.

At one point between airplanes I considered buying a 172. However, I like flying an airplane with a stick as opposed to a yoke, and having the ability to look almost straight down from both sides made the Citabria the clear choice.

My current airplane has an IFR panel with a Garmin GNX 375 GPS and aera 660. While I have flown it in hard IFR conditions I mostly try to avoid that. Hopefully, American Champion will have the TruTrak autopilot certified as a retrofit option soon.

For a Saturday burger run or a trip to the back country, you just can’t beat a Citabria.

John Ewald – New Braunfels, Texas

I owned a 2007 Citabria for about 12 years and just sold it last year. I purchased it new and it spent its life as a trainer in several flight clubs. It was a blast of a plane although definitely not a cross-country one. I picked up the plane new in Wisconsin and flew it back to California. When it came time to replace the engine, I flew it to Ft. Worth to a friend’s shop where he swapped it for a factory-rebuilt one. From experience I can say that three hours in the plane and my rear would tell me that was enough!

The Lycoming 0-320-B2B 160-HP is really a bulletproof engine and withstood the abuse of a life as a trainer without any complaints. I finally replaced the engine at 300 hours past TBO due to a flying club insurance requirement; I hated to do it as it still ran like new, had good compressions and didn’t use oil.

The airframe itself isn’t as bulletproof as the engine. One weak spot is on the longerons near where the gear bolts attached along with diagonals from the upper frame. The cracking at that point is enough of a recurring problem that the factory has a service kit to reinforce that point. The kit is reasonably priced, but it is a major repair to have this done, which involves removing the fabric. Prospective buyers who don’t have experience with fabric planes need to keep in mind that they won’t take the abuse of years of sun and weather like an aluminum plane does.

I really hated to let it go, but it was time to let it retire to an easier life. The plane was so much fun to fly and the view was like flying in a fishbowl. It was easy to taxi with ample forward visibility. With the 160-HP engine it climbed like an elevator, and with proper energy management would easily do loops and rolls.

Will Lewis – San Carlos, California

Our thanks to Will Lewis for the cool shot of the Citabria in our lead photo.

In 1995 I picked up my new Super Decathlon at the factory and flew it for 23 years and 1500 engine hours with no damage history. It only had a single leaky intake valve as an engine problem before I flew it to Illinois and its new owner in 2018.

Champion Aircraft’s head rode with me before releasing me, not wanting an airplane unable to successfully leave the factory airport in one piece. I found that I couldn’t keep pulling back on the stick after a three-point landing (especially with a heavy person in the back) because it would cause the tailwheel to lose its good geometry and shimmy. This was the only undesirable characteristic that stayed with the airplane.

I added the STC’d oil filter very soon and, because it was my only airplane for traveling as we’ll as aerobatics, an electric attitude indicator and heading indicator, which could follow me through a simple loop or roll without tumbling. I flew it around the country: Tucson, Arizona, Rapid City, Minnesota, around Florida and up the East Coast.

With a powerful rudder and considerable weight on the tailwheel (don’t try to lift it off the ground by yourself), it could handle significant winds, and never did try to go around on me when landing or taking off.

I never used it for competition but would aerobat it every time I was alone and the ceiling was adequate. With parachutes available from the first flight, I did give aerobatic instruction and rides fairly often. It was a nice spinning airplane and I enjoyed instructing pilots and nascent instructors in upright spins.

With spades, it was a lovely and fun rolling airplane—much faster than a beloved Stearman—but certainly not as rapid or as light as a Pitts or Eagle, all of which I had previously flown extensively. With the inverted system, all the available maneuvers (except inverted spins, which I didn’t do) were available within utility load limits, so it lived an easy life.

Will Hubin – via email