If you’re shopping for a used low-wing four-place cruiser, the starting point might be the Cirrus SR20 or Diamond DA40. If they break the budget, there’s always a Piper Archer. And for the right one, that’s not a bad compromise.

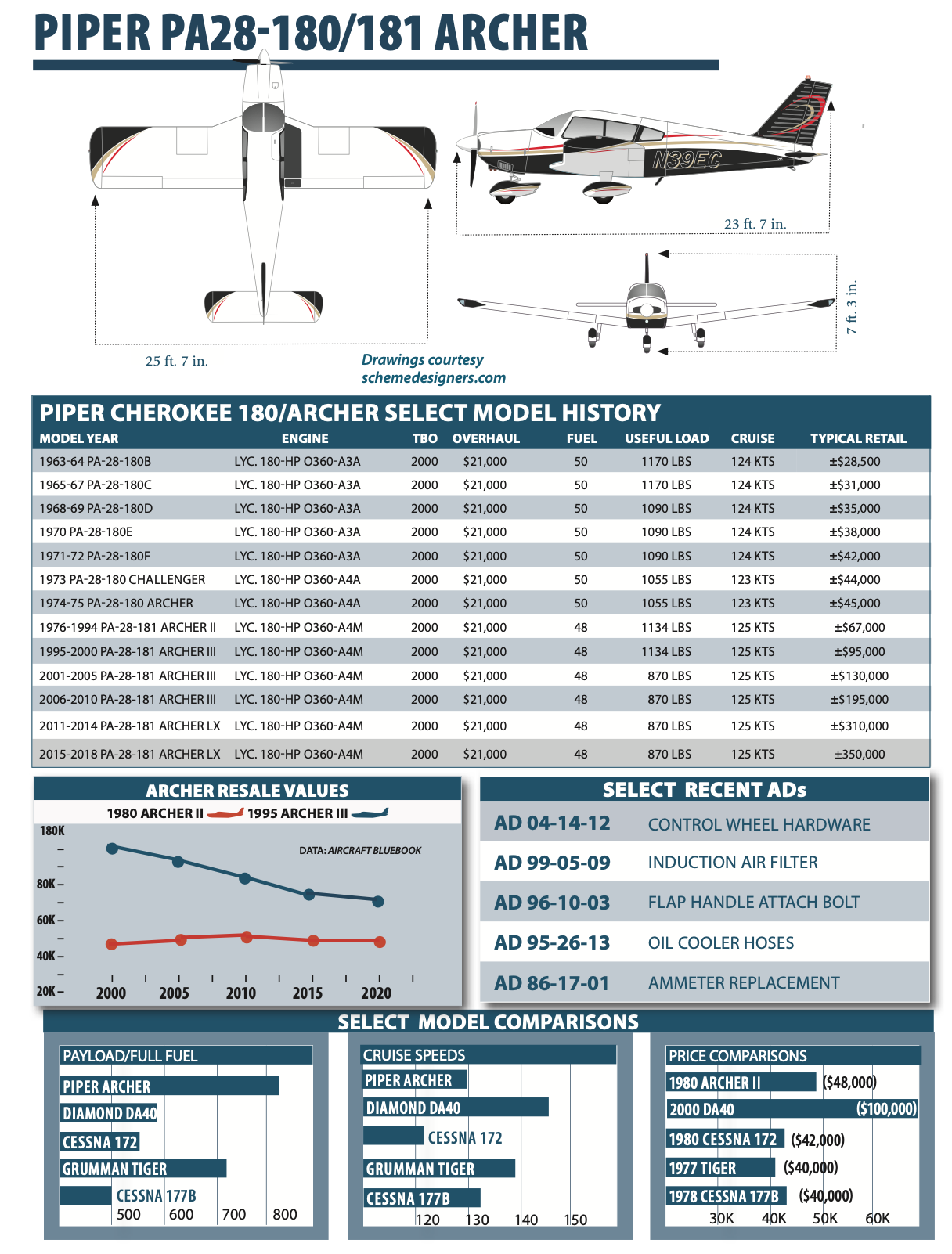

The current market has a wide variety of venerable Piper PA28-180/181 models for sale, typically priced from $28,000 for an early 1960s 180B to nearly $385,000 for a late-model Archer DX.

Don’t worry about field support. Piper seems to have it covered, plus what experienced mechanic can’t work on a Cherokee and its Lycoming O-360? Here’s a look at the current market and what to consider when adding one to the hangar.

HISTORY

The PA-28-180/181 series, of course, can trace its roots back to the basic Cherokee 140 and point to close relatives like the Arrow, Cherokee Six/Lance/Saratoga and even the Seminole twin. All owe their existence to the first Cherokee airframe originally designed by the late John Thorp, best known for the crank-winged Thorp T-18 homebuilt, among his many other designs. He reportedly considered the PA-28 among his favorites and, if viewing an original copy in plan form, one can easily see the resemblance between the first Cherokee and the Thorp T-18.

And this Piper’s lineage highlights something Piper has always done well, perhaps better than everyone else: Build a good basic model and evolve it into improved follow-on products without greatly increasing manufacturing costs. First rolled out in 1963, the original Cherokee 180 has been upgraded considerably, but is fundamentally still the same airframe, with some 10,000 flying.

The first Cherokee 180 had the constant-chord Hershey-bar wing (span 30 feet)—so named because of its resemblance to the candy bar—and a Lycoming O-360-A3A engine. That early engine had a TBO of only 1200 hours, mainly due to a weak valve-train design, including 7/16-inch exhaust valves, which was far from Lycoming’s best effort. Later, those engines were switched to ½-inch valves, which increased the TBO in part by eliminating chronic issues with excessive wear and heat-induced damage. The smaller valves long ago should have been flushed entirely from the market by overhaul or remanufacture, but prudent buyers will check anyway if looking at an older engine.

The newer engines all carry Lycoming’s more-or-less standard 2000-hour TBO, and the overall engine has a well-earned reputation as one of the company’s—if not the industry’s—more bulletproof designs. In fact, the engine’s reputation is one of the reasons for the Archer’s ongoing popularity. Throughout its history, the PA-28-180/181 has used essentially the same Lycoming O-360—still 180 HP—with only minor variant changes, although many wish for fuel injection.

After five years of production and few airframe changes, the instrument panel was modernized and a third, trapezoidal window was added to each fuselage side in 1968. This resulted in the airplane’s current ramp presence while admitting more light into the cabin. A longer wing came along in 1973—still with a constant chord, though—accompanied by a bigger stabilator and a five-inch fuselage stretch. The extra inches made a noticeable difference on cabin space.

At the same time, a modest, 50-pound boost in gross weight (to 2450 pounds) improved the airplane’s payload by half a person while a larger door, more-crashworthy seats and additional panel improvements rounded out the cosmetic improvements.

For 1973, the Cherokee 180 became the Challenger, but that wasn’t a Native American name, so Piper quickly changed it again—to Archer, beginning with the 1974 model year—continuing its ongoing theme. (Neither of those strictly are Native American names either, but despite the illogic, Piper’s are perhaps easier to follow than Mooney’s.)

It wasn’t until 1976 that the new tapered wing—still the standard configuration today—was introduced to the 180-HP airframe, resulting in the type-designation change to PA-28-181, which also continues with the current model. This change was so significant the model received yet another name: Archer II. Subsequent-manufacture PA-28-181s are known as Archer IIIs, while the latest Archer is the LX.

The basic tapered wing first was installed on the then-new 1974-era Warrior and, after a few tweaks involving the aileron control system, was added to the company’s other PA-28 models and, eventually, to the PA-32. The new wing’s inner panels were still constant-chord, while the outer panels were both lengthened and tapered. Wing-mounted fuel tanks remained in the same location, although total unusable fuel increased by two gallons.

The Archer II got a powerplant change as well, to the -A4M version of the 180-HP Lycoming O-360. That same engine is installed in new Archers today. These changes, of course, brought escalating prices. An original, 1974 PA-28-180 Archer with average equipment brought in $23,495 to Piper’s coffers while a typically equipped 1980 Archer II sold for $47,610.

There was no 1991 Archer, as Piper became ensnared in the light-aircraft industry’s overall economic troubles, but by 1995 a reinvigorated and rebranded company—New Piper—rolled out the Archer III. It sold for $181,700, again with average equipment installed. We’ll always remember plucking one of the first Archer IIIs from the Vero Beach factory ramp during a ferry mission, while marveling at its modern appointments, compared to the early ones we grew up with.

By then, the New Piper Archer III got an upgraded cowl, an all-metal instrument panel, factory-installed Garmin GNS 430/530 navigators, new paint schemes, air conditioning, better seats and an improved exhaust system. A 2010 model retailed for $299,500, and came standard with an Avidyne Entegra glass panel, an S-TEC 55X autopilot, air conditioning and two Garmin 430W navigators.

Priced in the low $400,000 range, the current Archer LX has Garmin’s G1000 integrated avionics (standard are two 10-inch displays), electronic engine indication system, a backup EFIS system, plus an ultra-modern paint scheme. It still has Lycoming’s O-360-A4M engine mated to a Sensenich two-blade propeller.

Speaking of engines, in 2014 Piper unveiled the Archer DX at the Aero show in Friedrichshafen, Germany. It has Continental’s 1200-hour TBO and FADEC-controlled CD-155 diesel.

LOADING AND PERFORMANCE

For 180-HP airplanes, Archers haul respectable loads. Empty weights vary by year and example, of course, but one owner told us his PA-28-180’s empty weight was 1452 pounds on a gross weight of 2400 pounds. With full tanks, that allows 650 pounds of people and stuff, or three husky people and a bit of baggage. Not bad.

Later Archers allow a 2550-pound gross but empty weights are often higher, so payloads are lower. A 2010 Archer III with standard equipment weighs in at a hefty 1688 pounds empty with a ramp weight of 2558 pounds, for a useful load of 870 pounds. Older Archers might beat that by 75 pounds or more. With four people in the airplane and, say, 50 pounds of baggage, a typical example has room for 35 to 40 gallons of gas, or about three hours’ endurance with 45-minute reserves. Again, not bad for a modest airplane. If the passengers are light, full fuel and full seats may be possible.

Performance-wise, the Archer is respectable, but no one will mistake its numbers for a Bonanza’s, or even an Arrow’s. How fast you go on 180 HP depends on the year of manufacture and the equipment. Specifically, the semi-tapered wing on the 1976 and later Archers yielded benefits at both ends of the airspeed spectrum. The stall dropped by 4 knots and cruise speed went up by about the same amount. The large wheelpants available in 1978 add another 4 knots or so to cruise speed.

Even so, a late-model Archer with wheelpants will cruise at only about 120 knots, although some owners insist they see 125 to 130 knots. (We suspect erroneous airspeed indicators or tachometers.) The airplane gives up 10 knots to a Tiger but pulls ahead of a Cessna 172. Climb rate, while better than a 172, isn’t stellar. According to the POH, the airplane will climb out from sea level at about 740 FPM but, by the time it reaches 6000 feet MSL, upward mobility has trended off to around 450 FPM. As many owners attest, original Archers with the Hershey-bar wings eke out slightly better rate-of-climb numbers than later models with tapered wings.

The nosewheels are steerable on the ground, and the rudder pedals come with conventional toe brakes. Parking or emergency braking is controlled by a meaty handle and locking mechanism just to the left of the center console and easily manipulated with the pilot’s right hand.

Unless the airplane is air-conditioned, summertime cooling of the occupants can be a problem on the ground and at low altitude. Fresh-air ventilation is via wing-root inlets with outlets above the floorboards, supplemented by fan-driven overhead vents getting fresh air from an inlet at the top of the vertical stabilizer. Neither works we’ll on the ground, requiring an open-door policy until right before takeoff. The good news is the Archer’s heating system usually works well.

Piper long ago abandoned its overhead pitch trim control—pilots never could remember which way to turn it to get what they wanted—and put a conventional wheel on the center console, between the seats. Below the instrument panel, in a center pedestal, is a rudder trim knob, though it’s not always necessary.

Early airplanes came with a double stack of avionics, with less-critical boxes mounted in a second column to the right of center. Again, many of these airplanes have since seen an avionics shop for upgrades, but many others haven’t. Reaching to the far side of the panel isn’t a chore, but it’s an inconvenience and something you should consider for a potential purchase. Recent upgrades may have eliminated boxes from the right stack, but unless the entire panel was redone, cosmetics may suffer.

Wing flaps are controlled with a Johnson-bar handle between the seats, including detents. It’s an easy system to deploy smoothly, while also affording the ability to immediately retract or extend flaps, depending on your needs, without having to wait for an electric motor. And, of course, they’re fully available even in the event of an electrical failure. Deploying flaps does result in an upward pitching moment, but it’s relatively easy to counteract with forward pressure on the yoke. Most crosswinds are easy to handle, thanks to the low wing and wide gear.

Early airplanes mounted the circuit breakers to the far right of the instrument panel, about as far from the pilot as possible. Same with the heat/defrost controls. On the upside, frequently needed switches—master, fuel pump, beacons and the like—are mounted just above the engine controls. System gauges are just below the flight instruments, with an idiot-light annunciator panel above them. The tachometer is mounted in front of the pilot’s right knee, which often makes for unnecessary head motion during takeoff.

COMFORT AND HANDLING

Occupants should have no trouble remaining comfortable during a three-hour leg, although pre-1973 back seats—before the five-inch fuselage stretch—are somewhat tight. Pipers have decent but not exceptional front seats with an S-shaped frame designed to absorb energy in a crash. The height adjustment uses a gas-assisted spring and when this wears out, the seat automatically falls to its lowest setting, giving a short pilot a good view of the glareshield, but little else.

The seat stuffing tends to compress with use, causing sags, and the plastic back trays on the seats aren’t at all durable and fall apart with use. The aftermarket is your friend, as relatively inexpensive solutions exist for both well-known issues. There’s an adequate baggage compartment behind the rear seats that’s accessible in flight, but can’t be opened from the inside.

Cabin appointments can range from the original avocado green or bright orange upholstery and sub-panels dating from the 1970s to more tasteful and less jarring designs, including what seems to be the new industry standard: light gray fabric or leather. Later models came with all-metal instrument panels—the Royalite plastic overlays were finally banned.

The Piper Cherokee didn’t get to be an industry-standard airplane by having handling quirks; it simply has none. Its flight controls are relatively we’ll balanced, with roughly equivalent pressures required in all three axes. The Archers are safe, stable and predictable and easy to land, even on short runways. In slow flight, the airplane has no bad habits, nor does it build speed in unusual attitudes.

Despite the tapered wing’s better looks and—as many pilots confirm—its improved roll response, the market hasn’t always treated the Archer II well. In fact, there’s not much difference in performance between the Hershey-bar-winged versions and the tapered wing. The original Archer wing’s span of 32 feet increases to 35 feet, five inches on the Archer II after it’s tapered, while the service ceiling decreases and takeoff ground roll increases. Distance to clear a 50-foot obstacle is markedly reduced by tapering the wing, however, as is stall speed.

Those numbers—and perhaps the ability to use a smaller hangar—probably explain why clean, early Archers—the 1974 and 1975 models—today sell in the $50,000 range, according to 2019 trends, while their slightly younger brethren fetch less, on average. The deficit isn’t overcome until the 1980 model but—all things being equal—prices start escalating from there. By comparison, a 1980 Cessna 172 retails for about $45,000 while a Grumman/GA Tiger of about the same vintage sells for around $50,000. You can’t touch a newer Archer III for under $100,000, in general. Want a DX with the Continental CD-155 diesel? They’re out there starting in the mid-$300,000 range, and the 1200-hour TBO engine has a typical overhaul price of $50,000, according to the latest Aircraft Bluebook.

MAINTENANCE

Archers don’t have much AD baggage. It was the target of a controversial AD in 1987 calling for an expensive inspection of the wing spar for cracks. This procedure required de-mating the wings and cost some $1200 at the time. In typical FAA overreaction, it was an emergency measure brought about by the crash of a 7000-hour Archer used for pipeline patrol. That AD was rescinded when the expected rash of cracked spars failed to materialize.

However, in reviewing recent service difficulty reports, we noted that mechanics are finding evidence of corrosion in the spars, at least one of which required replacement. This corrosion is often discovered when leaking fuel tanks are removed for repair. Make sure a prebuy includes an inspection and check the wing-attach fittings, too.

Check the baggage door for a leaking seal; the telltale sign is wet or water-stained carpet on the baggage floor. By now, early Archers should have been through at least one interior refurbishment, so pulling up the floorboards in that area to inspect for corrosion is a good idea.

While you’re back there, take a few extra moments to inspect the battery box just aft of the baggage compartment. Piper placed it there, presumably, to help with loading. But in a misguided effort to save weight, the company at one time equipped its airplanes with aluminum battery cables, which proved susceptible to corrosion. Given the lengthy cable run from the battery box to the engine compartment, many owners have encountered starting issues. Aftermarket kits and a Piper service bulletin are available to help replace the aluminum cables with copper, which isn’t as prone to corrosion and high resistance.

Another problem is leaky fuel tanks, particularly on older airplanes. An airworthiness directive (AD 79-22-02) addresses peeling tank sealant, with which owners long ago should have complied. It’s not much of a problem any more, certainly nothing like the hassle of owning a Mooney. The vents are also a source of maintenance trouble. One SDR found they had been installed incorrectly.

Otherwise, maintenance hotspots have to do with typical Lycoming issues, such as cracked cylinders, corroded cams and problems with Bendix and Slick magnetos. Also, on older airframes, the stabilator bushings may need work. Have them checked during prebuy. Another area to look at, according to the SDR database, is cracking in the skins of the forward wing walk. One SDR submitter reported six high-time airframes with this damage.

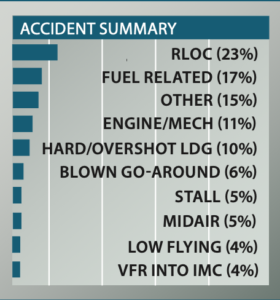

After reviewing the 100 most recent accidents involving the Piper PA28-180/181 series we found ourselves feeling sorry for the airplanes. In the pilot/airplane flight partnership, the Cherokee 180s and Archers generally held up their end of the deal—there were only eight accidents resulting from something wrong with the airplane (engine stoppage).

On the other side of the equation, pilots found many ways to wreck what we consider to be an honest line of airplanes.

Continuing to look at engine stoppages, the 180-HP Lycoming has a reputation for not being susceptible to carburetor icing. However, it’s not immune—two airplanes were brought down by carb ice and pilot inaction.

We’re cynical, but we were still astonished by the one other engine/mechanical accident. When investigators started looking at a forced landing following the loss of part of a propeller blade, they found that 17 years prior to the accident the prop had gone into a prop shop for work. The shop found the prop to be unairworthy and returned it.

The owner put the prop back on the airplane. Twelve years before the accident, an AD was issued requiring inspection for the condition that caused the eventual failure. The owner ignored it.

Somehow we can just hear the owner now, “Hey, that prop shop didn’t know squat. I got 17 years of service out of a prop they said was unairworthy.”

There were 23 runway loss of control (RLOC) events. That’s slightly high for a tricycle gear machine, but not surprising as the majority involved student pilots.

We found six runway overrun accidents. The airplanes will float, especially when landing with partial flaps and extra speed.

There were only five stall-related accidents, most on high density altitude takeoffs at or near gross weight. One of those followed an intersection takeoff.

We consider 17 fuel-related accidents to be a high rate. Most involved pilots simply running the airplane out of fuel. One pilot who “wasn’t comfortable with leaning procedure” unsurprisingly ran the tanks dry after cruising with the mixture full rich.

In response to a CFI setting up a practice forced landing, one student followed the checklist and changed fuel tanks. Unfortunately, he inadvertently positioned the fuel selector between detents. He got to experience a real forced landing.

While pilots like the manual flaps for the ability to rapidly extend them, there’s no free lunch. The flaps can also be rapidly retracted. Mistakenly doing so put three airplanes into the ground, hard. Two came after takeoff. The third occurred after a CFI took the controls and initiated a go-around when the student had problems on landing. While still low and slow, the student retracted the flaps.

We felt for the instructor who took the controls as a student’s swerves on takeoff became progressively worse. He got the airplane into the air and entered a turn to avoid obstructions beside the runway. The student then closed the throttle. Even though the CFI immediately firewalled the throttle, a wingtip hit the ground and ended the flight.

MODS

LoPresti Aviation (www.speedmods.com) has flap gap seals, wheelpants and flap hinge fairings. Met-Co-Aire (www.metcoair.com) offers replacement wingtips, tailcones and dorsal fins. LoPresti also offers its BoomBeam landing-light enhancement, which we find worthy.

Knots 2U (www.knots2u.net, 262-763-5100) also sells a range of Cherokee mods, including gap seals, wingtips and wheelpants. The company also offers upgraded strobe lights, engine air filters and aftermarket control wheels, among other products.

Laminar Flow Systems (www.laminarflowsystems.com, 386-253-8833) offers a wide range of gap seals, wheel fairings and other aerodynamic cleanup kits for the Cherokee. For fiberglass parts to replace broken or cracked plastic exterior fairings, of which the Cherokee has many, try Knots2U, and read the replacement plastic article in the October 2018 issue of Aviation Consumer.

There are two type clubs serving the Piper Archer models. The Piper Owner Society (POS, www.piperowner.org) consolidated its efforts with the Cherokee Pilots Association (CPA) several years back. The Piper Owner Society serves all Piper products and is a good source of tech and operating information. Meanwhile, the Piper Flyer Association (PFA, www.piperflyer.org) offers services similar to POS’. There’s also www.piperforum.com, with plenty of good discussion about these aircraft.

MARKET OVERVIEW

Given the wide range of model years and histories of used Archers, it should be expected they will vary widely in installed equipment. Unlike Cessna—which only installed its house-brand ARC avionics in new piston singles until selling the unit in 1983—Piper put into its Cherokees either King or Narco products for quite some time.

A recent scan of the popular and respected sales website www.controller.com revealed quite a few earlier models still equipped with orphaned avionics, plus a mix of old and new. We found some models still sporting old-school gear like King KX170Bs, Narco MK12s, plus lots of new stuff including Garmin G5s, Avidyne IFD navigators and other latest retrofit products. Prices are all over the board, seemingly driven by these recent avionics upgrades—some impressively equipped with high-end autopilots, primary EFIS and big-screen engine monitors.

We think any would-be owner wanting to upgrade from a basic trainer—or even looking for an affordable entry-level airplane to use as a trainer, then as a platform with which to perform the weekend getaway—always should at least consider an Archer. It’s a bit faster than a Cessna 172, it climbs better and it carries a smidge more, all without gulping fuel the way a 182 does.

OWNER COMMENTS

I am in a 1974 Piper Archer partnership and from my experience, the Archer strikes a wonderful balance of performance, payload and efficiency. The Archer is no Mooney or Bonanza, but frankly, unless you are regularly flying 500-mile trips, you won’t notice much difference. I just keep thinking that with a faster airplane, I would get to fly less!

The stabilator makes the plane easy to fly in the pitch axis, making it a good instrument trainer. Our plane has a useful load of about 940 pounds and is nicely equipped with modern avionics, including a Garmin GNS 430 navigator.

I’m surprised at how efficient the airplane is to fly. I often return from local flights having burned 6 to 7 gallons of fuel per hour. If you would have told me that this was likely in anything but a Cessna 152, I would not have believed it. Of course, I lean aggressively (including on the ground), which also keeps the plugs clean and the magnetos smooth.

This plane is perfect for just poking holes in the sky in an inexpensive way.

Hish Abouelleil – via email

I’ve actually owned two Piper Archers before upgrading to a Piper Seneca II twin, and the Seneca was mostly an easy and familiar step-up. When I look at my operating costs I sure miss the Archers. They were cheap, by comparison, in every way.

My last one was a 2005 Archer III that I purchased new and it was far more modern, at least from an ergonomics standpoint, than my earlier one. It had decent high-back seats, a flat metal instrument panel and overhead rocker switch panel. I kind of felt the fit and finish could have been a little better, though, especially the interior components.Some of the plastic began to crack.

But what I really wanted was fuel injection. It always baffled me that Piper didn’t send late-model Archers out the door with the fuel-injected IO-360. To me the airplane was just a dressed-up version of the plane that came off the line in 1963.

Joe Griffin – via email