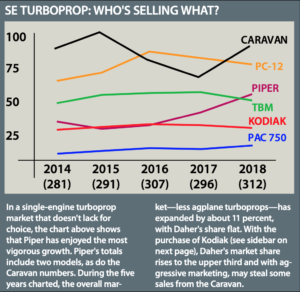

Cirrus and Daher, builder of the TBM turboprop, have different aircraft design philosophies, but they share one thing in common: Both build and sell airplanes to a select, moneyed clientele who seem perfectly happy to trade in a relatively new airplane on the latest new model. Call it community-style marketing. The sales guys know their clients by first name and N-number.

The latest new model from Daher—the TBM 940—continues this incrementalist tradition with a new airplane that’s outwardly little different from the previous model, the 930. Under the cowl, it’s another matter.

Debuting last spring at Sun ‘n Fun and Aero in Friedrichshafen, Germany, the 940 added an autothrottle to a class of airplane that’s finally beginning to see such technology fully integrated into power management. Within a few months of that announcement, Piper and Garmin revealed their own version, but with a stunning distinction: emergency autoland capability. Cirrus has announced the same for the Vision Jet and although neither are yet certified for operation, they’re expected to be shortly. Daher has no choice but to offer autolandl, too, and soon will, as an option on the 940. The company’s Nicolas Chabbert said no formal announcement has been made yet, but customers are being told they can have it when it’s ready and I’m sure buyers will check the yes box when asked.

For both Piper—who offers autoland in the new M600/SLS—and Daher, we’re told autoland is a game changer in ginning up sales potential. That may or may not be true but the larger game to be changed is what this technology opens the door to: Eventual full-up, pilot-optional autonomy.

No one really knows how far off that is, but Garmin’s autoland system clearly shows the airplane end of the equation is manageable. For the time being, TBM buyers can take a tween step with fully automated engine management.

BIG AIRPLANE FEATURE

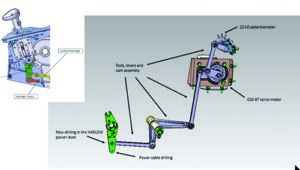

Autothrottles have been standard equipment on jet transports for decades, fully integrated into the flight management systems that are standard equipment on these aircraft. The technology trickled down to business jets and, lately, turboprop twins and singles too, with the introduction of the IS&S autothrottle system for the PC-12 and King Air models a couple of years ago. Mechanically, it’s not especially complex or involved. Garmin designed a servo to operate the TBM’s PT6A-66D’s throttle through a mechanical interconnect. It is not, however, throttle by wire. There’s still a hard mechanical connection between the cockpit power lever and the engine throttle lever. Nor is it true FADEC, although the integration with Garmin’s G3000—the complicated part—makes it almost function that way.

Garmin’s GSA 87 servo is connected to the engine throttle lever through a cam arrangement that does two things: It physically (and visibly) moves the throttle during power changes and it allows the pilot to physically disconnect the system, either by overpowering it or with a button on the throttle lever and panel.

Along with that hardware change, there’s also a new control unit called the GMC 711, an evolution of the GMC 710 which occupies the same real estate high on the panel just under the glareshield. The 710 had a speed button, but in the new version, that has been removed in favor of a function selector knob allowing either manual use of the autothrottle or FMS mode use. Garmin also shoehorned an additional button into the controller labeled AT. It toggles the autothrottle on or off and reiterates the button on the throttle lever.

The AT version of the G3000 also gets some significant display changes intended to reduce pilot workload while at the same time integrating the pilot’s attention to what the autothrottle system is doing. The display automatically shifts tabs around to suit the phase of engine operation. For example, on startup, ITT is critical, so that’s emphasized.

On takeoff or other phases of flight, torque indication is more important so it’s given prominence. The display also has some new CAS messages for out-of-limit engine parameters.

DIFFERENT THINKING

When I flew the TBM 940 out of Daher’s headquarters at Pompano Beach, Florida, Nic Chabbert explained that pilots will need several hours of training to master the autothrottle and get the most benefit from it. Daher thinks this is better done in the airplane than in a simulator. Oddly, it’s not so much that the pilot has to do much—he or she is actually doing less—it’s just that without understanding the system, it can be confusing to see it do its own thing uncommanded.

It’s also critical to grasp in addition to being a workload reducer for the pilot. Daher sees the autothrottle as an enhancement of the envelope protection the company has improved on in recent years. It has marketed this capability as the TBM E-Copilot and includes over-banking protection, stall mitigation—including a stick shaker—and emergency descent mode, a feature it developed after a high-profile accident that appeared to have been caused by a pilot incapacitated by hypoxia. The autothrottle’s capabilities are now rolled into those always-resident autopilot subroutines.

TWO MODES

The autothrottle can be engaged in one of two modes, FMS or manual. In the FMS mode, throttle management is as close to full-up automation as pilots are likely to see in any aircraft at this stage of development. We used this mode when departing from Pompano’s Runway 10. Chabbert explained that the FMS can be set up with a destination, waypoint and altitude in mind and all the pilot has to do is take off manually, switch on the AP and monitor.

On takeoff, advancing the throttle to 70 percent torque signals the AT to take over from there and it will automatically set the appropriate power for the rest of the roll and the initial climb. Once you’re used to it, this has an obvious benefit. You can concentrate on looking outside and holding the centerline rather than worrying about niggling the power setting or over-torquing. If you’re paying attention to business, you won’t notice the throttle moving on its own, but it is.

For a pilot new to the TBM, the thing accelerates and climbs so quickly that it’s easy to get behind it. Way behind. Even for an experienced TBM pilot, the AT helps because it frees up mental bandwidth for traffic scanning, radio work or other cockpit workload. It has some built-in smarts.

It knew, for example, that the airplane was still in Pompano’s Class D airspace and when I pitched over to meet a 1500-foot altitude restriction, it automatically—and smartly—cranked the power back to hold the 200-knot indicated speed requirement. Once we cleared the Class D, it throttled back up to resume an optimum climb, even though we weren’t headed to the flight levels. But had a route and higher altitude been plugged into the FMS, the AT would have handled all of the power setting at the appropriate moment.

“It’s a system that’s either zero or one. You choose to go manual or you choose to go through the FMS. We take off on FMS because the system knows where you are and what you want to do,” Chabbert explained.

In manual mode, the AT can be set up for target speeds. It will simply take care of setting the power while the pilot worries about heading or altitude bugs, or flies manually. At any point, the autothrottle can be knocked offline by pushing the throttle-lever button or the engage button on the panel. But not entirely offline.

ENHANCED E-COPILOT

The AT system figures prominently in the TBM’s envelope protection feature, the E-Copilot system. Daher’s iteration of this capability includes an emergency descent mode, which automatically descends the aircraft from high cruise altitude and turns it 90 degrees off course if it detects cabin pressure loss and the pilot doesn’t definitively respond to an aural and visual annunciation. The purpose of the turn is to alert ATC and potentially steer the airplane away from traffic on a busy airway or arrival.

Chabbert says giving the autopilot control of the throttle enhances the performance of emergency descent. “The autothrottle will always go to zero and then the autopilot to max Vmo of 260 knots. Once it reaches 15,000 feet, it will readjust to 50 percent,” he says. This results in a faster, smoother descent to 14,500, which is deemed sufficiently low for a hypoxic pilot or occupants to recover and resume control of the airplane.

The AT figures in over- and underspeed protection, too. If the aircraft gets slow and nearing the stall regime, the AT adds power first, before activating the stick shaker and eventually pushing the nose down. In overspeed situations, it can reduce the power to flight idle while the pitch servo gets the nose pointed up.

I wasn’t given enough time in the demonstrator airplane to gain any sense of how AT will affect approach and landing performance. Coupled approaches are nothing new and although I’ve never found data to support it, they certainly improve the technical quality of instrument approaches over those flown by hand. However, most pilots click off the autopilot at MDA or DA on an ILS and take it from there manually. That’s where the trouble starts because the throttle and trim are reset, upsetting the stable speed.

However, the TBM’s autothrottle can be set at the ideal speed-—say 85 knots—then just flown to the threshold automatically at that speed. Chabbert told me he flies an AT-engaged approach right to the numbers and clicks off the system with the throttle button as he reduces power for the flare. Landing accidents in high-performance aircraft occupy either side of a divide between being too fast or too slow on approach.

The TBM doesn’t have a well-defined accident pattern because it hasn’t suffered many accidents. However, at least two have involved stalls or stall mushes on approach. Between the AT and the underspeed protection, the airplane ought to keep all but the most clueless pilot from wandering into that trap.

OTHER IMPROVEMENTS

Early 940s were shipped without the AT, but Daher developed a kit for field upgrades. Previous models can’t be converted, however. In addition to the autothrottle system, new production 940s get an improved radar in the Garmin GWX 70, which includes turbulence detection and ground clutter suppression. There are also some new interior options. When autoland becomes available, it will be offered as an option on the 940, unless Daher changes its mind and adds something else to make it a new model.

Daher sees the 940 as both an incremental feature addition that adds utility and safety to the airplane and a transition to a new era. Once trained up on it, the autothrottle is definitely a workload reducer and limits worries about overspeeding or over-torquing. Whether that makes it a stronger seller against Piper’s M-Class turbines or the Pilatus PC-12 is irrelevant. If those airplanes have autothrottle, Daher can’t not have it if it expects to be competitive. Ditto autoland.

“I think it adds one more argument to the single-engine operation or for people who are looking at single engines being not as reliable,” Chabbert told me. “Statistically, all the data is showing that the single engine is extremely reliable. But the autoland is going to add another layer of protection and comfort level. But I believe the autoland is mainly addressing companion concerns,” he adds.

Chabbert says buyers almost universally spec fully equipped aircraft with invoices typically about $4.5 million. For more information on the TBM 940, see www.tbm.aero.