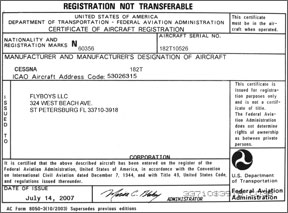

Prospective aircraft buyers must decide how to structure the ownership of the airplane. For an individual, the options are to put it in the owners name or to form a corporation to own the airplane. with the individual as the sole shareholder. (An L.L.C. is so nearly identical that we’ll use the word corporation to cover both.)

If there is to be more than one owner, the aircraft may be owned as a partnership, with each owners name showing on the registration, a limited partnership (so rare in general aviation that we’ll ignore it here) or as an asset of a corporation with the owners being shareholders.

The quick and dirty advice for which is best is simple: For an individual, a corporation does not provide any advantage unless the owner/pilot is doing significant charitable flying (medical mercy, environmental, etc.) and wants to use the available tax deduction for renting the airplane to him or herself. For group ownership, a corporation provides benefits that are worth exploring if the owners are willing to do the paperwork, reporting and file the required tax returns.

So Sue Me

When corporate ownership of aircraft is discussed, protection against personal liability is usually the first topic. Many pilot/owners believe that having a corporation own their airplane somehow provides magic liability should they have an accident while flying.

It doesnt. No matter how the aircraft ownership is structured, the pilot whose sweaty palms were on the controls at impact is the one who is facing personal liability if he or she were negligent and caused the accident. The protection against potential liability is insurance. If the airplane is a corporate asset, the insurance should name the corporation and each of the shareholder/pilots as insureds.

There is a liability benefit of corporate ownership when there is group ownership. In a partnership, each partner may be held personally liable for the actions of the other partners. In a corporation, the shareholders are not personally liable for the acts of another shareholder. Nevertheless, insurance is still the way to protect against liability-and cover the cost of defending a lawsuit.

(Corporate) Death and Taxes

For a corporation to remain viable there are annual filings required. Should they not be made the state may decide that the corporation is no longer in good standing and may act to end its existence and any benefits of incorporation will be lost. Setting up a corporation means being willing to comply with the annual requirements to keep it in existence.

Incorporation requires that a federal and (and usually state) tax return be filed annually, an expense for the corporation. It also may mean that the aircraft is depreciated. This can be a tax benefit for the shareholders, as most owners chose the subchapter S option so any corporate profits or losses flow directly to the shareholders, as is the case with an L.L.C. However, it also means that when the airplane is sold there may be a significant “gain” on the sale (sale price over the depreciated value). That can be quite a tax hit for the shareholders.

Sometimes an aircraft will be sold as a corporate asset. The buyer just buys all the shares of the corporation and gets the airplane in the deal. Its one technique that is used to avoid sale tax on the transfer of an airplane because the owner of the

airplane remains the same, just the shareholder(s) change. It isn’t a 100-percent effective technique as some states charge sales tax on such a transaction.

Its also essential to review the books of the corporation before using the corporate-asset technique because the airplane may be depreciated to nothing, and the new owner may get clobbered on income taxes if he later sells the airplane and not the corporation. It is also essential to determine whether the corporation has any outstanding debts because those get acquired along with the assets (the airplane) when buying all of the stock.

The Other Sales Tax

A number of states have what is called a “use tax.” Somewhat similar to a sales tax, it requires that the owner pay a percentage of the value of the airplane when an airplane is brought into the state for a specified period of time (usually several weeks), if the owner has not already paid sales tax on the airplane. Some buyers choose to form a corporation in Delaware, which does not have sales or use tax on airplanes, thinking that they will avoid their states sales or use tax.

It rarely works. While the registration address for the airplane is in Delaware, the airplane is based in the buyers home state and is subject to use tax. A large number of states require that airport managers report the N numbers of airplanes on their airports each night, either based there or transient. The states see if the airplane sticks around long enough to bill the owner for use tax (something to be careful of if you have your airplane out of state for maintenance and it gets delayed a long time). With the tax-cut fad, most states are scrambling to find any way they can of making up the shortfall. Just one hit can result in thousands of dollars of revenue. The only good thing is that if you pay sales or use tax in one state, other states that may have a claim for a use tax must give credit for the tax you already paid.

The grim reality is that if your state has a sales or use tax, put that into your airplane purchase budget. Incorporating the airplane in another state wont help you evade it.

If your state has sales tax, plan on paying it. However, find out how your state values used airplanes. If it simply applies the Blue Book or Vref number and your airplane is either not airworthy, or is of substantially lower value than the book number, you may be able to get the assessed value reduced. Follow whatever procedure your state has in place. An estimate from a shop showing the cost of making the airplane airworthy may help.

If you buy an airplane and pay sales tax on it and then decide to put it into a corporation, most states allow you to do so without paying sales tax again. Youre using the airplane to capitalize a new corporation in which you are sole stockholder, If you try to put the airplane into an existing corporation, it is usually a sales-taxable event. If you form a new corporation to own the airplane with a stockholder that wasnt on the title with you, form the corporation with you as sole stockholder and then sell the other person some of the stock to avoid extra taxes.

If one of the members of partnership (each owner shows on the registration) sells her or his share to someone else, that sale is a sales-taxable event. A bill of sale and new application for registration must be filled out and sent to the FAA with the $5 filing fee. If a corporation shareholder sells her or his shares to someone else, that is usually not a sales-taxable event. Its simply the sale of some company stock. No action need be taken with the FAA as the corporation still owns the airplane. The FAA isn’t interested in the identity of the shareholders so long as at least 51 percent of the stock is owned by U.S. citizens.

Flying for Charity

If your airplane is owned by a corporation in which you own some or all of the stock, the net effect is that the corporation rents the airplane to you when you fly it and the corporation charges you a rental rate that covers the cost of ownership and operation of the airplane. That means record-keeping to keep track of income and expenses. For an individual owner, its generally not worth the time and effort involved.

The exception may come if you do a significant amount of charitable flying for which you wish to take a tax deduction. Renting the airplane may save you a healthy sum at tax time. The FAA and IRS have both made it clear that if you own an airplane in your name or as a partnership, and do a charitable flight, you may only deduct the cost of gas, oil and landing/tiedown fees for the flight. You have to eat the hourly share of maintenance, hangar rental, insurance, overhaul set aside, etc.

But, if you rent an airplane, you can deduct the entire cost of the rental for a charitable flight. As the true operating cost of the airplane is usually a multiple of the hourly fuel cost, the charitable deduction available for renting may be from two to four times that of the deduction if you can only count fuel and oil.

Groups Benefit Most

Putting this all together, corporations benefit group ownership the most. It provides tax savings should one shareholder want to get out or to bring additional pilot/owners in, and it limits personal liability exposure should one of the shareholder/pilots crash the airplane. Individuals get little benefit except with significant charitable flying, so the extra expense of corporate recordkeeping and filing is usually not worth the hassle.

No matter how you structure ownership, expect to pay your states sales or use tax as the operant issue is not where the corporation is based, but where the airplane spends its time on the ground.

Rick Durden is an Aviation Consumer contributing editor with an extensive background in aviation law.