When famed researcher-and inventor of the electric starter motor-Charles Kettering discovered that no compound worked as we’ll as tetraethyl lead to kick up the octane of gasoline, he couldnt have guessed that nearly 100 years later, science would still be looking for something almost as good. That the search hasnt born fruit is one reason-although not the only one-that we still fly behind magnetos, not the electronic ignitions that have been commonplace in cars for three decades. Its not for lack of trying. Teledyne Continental has had a certified FADEC for piston engines for some eight years, homebuilders fly with various iterations of electronic ignitions and General Aviation Modifications intriguing PRISM system thus far exists only as a test article. And the tests confirm that these ignition systems can prevent detonation in high power engines burning lower octane unleaded aviation fuels. So whats the problem?

Dwindling Supply

Curiously, the aviation industry is at a similar crossroads as Kettering was in 1919 when General Motors set him off in search of an octane booster. As is the GA industry now, GM was worried that gasoline supplies would soon run out and the industry needed a way to both improve poor quality petroleum-based fuels and to use ethyl alcohol as a primary fuel. Alcohol has poor anti-knock qualities and of thousands of compounds tested to improve alcohols anti-knock qualities, nothing came close to tetraethyl lead. By the early 1920s, it was the standard for octane boosting.

But the Clean Air Act of 1970 forced automakers to rely on catalytic converters to meet emission standards and because lead fouled the converters, it was phased out of motor fuels. Except for airplanes, which at the far end of the performance/horsepower spectrum, still rely on Ketterings TEL for detonation margin. Nearly 90 years of advances in chemistry and physics havent changed that.

“As far as additives go, what youve got is what youve got,” says Earl Lawrence, who follows fuel issues for the Experimental Aircraft Association. On a trial basis in the U.S., the industry has produced unleaded aviation fuels in the 95- to 96-octane range and these are economic to blend and distribute. Thats good enough for low-horsepower, lower compression engines but higher power engines still need 100 octane, or near it. Lawrence told us exotic additives have been tried in the struggle for 100-octane numbers but, just as Kettering discovered, these compounds arent economically practical. Complicating the issue is the headlong rush to add ethanol to motor gas, which many pilots burn in airplanes approved for it. Ethanol damages rubber and fuel components in some aircraft.

Retard the Spark

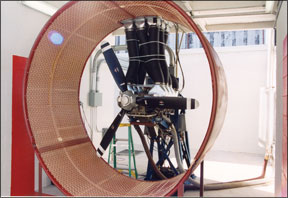

With the thrust for additives somewhat stagnant, the industry has sought a

mechanical solution in the form of ignition systems that build in detonation margin by selectively or reactively retarding spark timing. This slows the propagation of the combustion flame front and reduces the likelihood of destructive detonation.

A start-up company called Aerosance-now a Teledyne Continental subsidiary-got on the ignition bandwagon early and by 1998, it had developed a nearly certified electronic system which eventually evolved into TCMs PowerLink FADEC.

The Aerosance system can best be described as an automotive-type approach, using a combination of pulsed fuel injection and variable ignition timing. Part of PowerLinks reason for being was to accommodate lower octane fuel so ultimately, its designed to be a closed loop system with knock sensors. Aerosances CEO, Steve Smith, told us the system has been demonstrated with this capability and although it can be made available, it hasnt been yet. Why? Lack of demand.

“We had always thought it [FADEC] would be worth it for fuel savings and because it results in a smoother running engine, but nobody seems to be buying that,” Smith told us recently. To date, there are about 200 PowerLink systems flying on e xperimentals and on XL2s from Liberty, the only OEM thus far committed to FADEC. Diamond says it will also use the PowerLink system in its new DA50 Superstar and other OEMs are nibbling but not biting.

A second electronic ignition contender, GAMIs PRISM system, is into its fourth test generation, but hasnt flown. PRISM is also a closed loop system, but it leaves the fuel system alone and anticipates detonation by sensing rising cylinder pressures, retarding ignition timing accordingly. Its not market ready, either. One reason is the enormous capital necessary to certify it into a market that has thus far showed

tepid interest.

“When youre developing these things, you worry about opening up the newspaper one morning and reading that someone has developed a new 100-octane additive that will make lead go away,” says GAMIs George Braly.

Although that seems unlikely, the fuels industry may have gotten just close enough to obviate the need for a full-up FADEC for detonation protection-these are 96-octane unleaded fuels.

New Departure

For that reason, both TCM and GAMI are considering different tacks to make electronic ignition appealing. TCM thinks the future selling point will be less detonation protection and more the sophisticated maintenance diagnostics that an electronic system can provide. Theyve already demonstrated the ability to download dozens of engine operating parameters for diagnosis, just as the typical auto dealer does with a BMW or even a Ford.

“You can go out and fly your airplane, pull it into the mechanic and he can pull out his laptop and read out engine performance results. Depending on what diagnostics hes running, we can begin to see what the engine is doing. Its a very neat opportunity,” says TCMs new president, Rhett Ross.

GAMIs Braly is contemplating a less intrusive system that might be thought of as PRISM Lite. Rather than a full-blown system with pressure sensors for detonation detection, this system would sample induction temperature, CHT and manifold pressure and through some canny software, it would retard ignition timing to build in detonation margin.

“Give me just a little bit of hardware, and I think we can do that,” says Braly, who

adds the system would be cheaper to certify and produce than a full-blown FADEC. That might be critical if electronic ignitions are ever going to see widespread acceptance.

“Three years ago, I thought we could produce PRISM for twice the price of a Bendix 1200 magneto. I don’t think we can do that,” Braly told us. The realistic multiplier is three to five times the magneto cost, meaning $10,000 on the low side, but under $20,000 at the upper end. The unknown is whether buyers will see value enough in those prices to dump magnetos in favor of electronic ignitions.

Absent that, Braly thinks it will be a difficult market. Despite the suggestion that FADECs will improve fuel economy, he believes the gains would be too minor to make investing in an electronic ignition worthwhile. By operating lean of peak and with magnetos, owners can already enjoy best-case fuel specifics in the .38 to .40 BSFC range. Electronics might improve that marginally, but enough to invest $10,000 to $20,000?

Our guess is no-unless the disappearance of 100LL forces the issue for that small percentage of aircraft owners who cant burn unleaded 96-octane fuels. And that brings us full circle back to Ketterings 1919 research bench. Until 100LLs fate is determined, FADEC may reside in limbo for awhile.