by Dr. Bob Glass

Its 0400 Zulu. A dark night, but its a VFR flight with clear skies and unrestricted visibility. You pull out the sectional to look up the ATIS and Class-D tower frequencies. You look twice. Whats that say? Is it a 12…or is that a 3? Better turn on the cabin light, squint a bit more. Oh, boy.Wheres that magnifier?

Has this ever happened to you? If youre over 40, if it hasnt, it will. That is, unless your AME catches it first. There’s even a name for it: presbyopia.

Literally translated, it means old eyes. But don’t despair. When the name was coined about a hundred or so years ago, people didnt usually live to be over 40, so if you were lucky enough to be old, you got this condition.

Well, now we have the privilege of extended life expectancies. Forty is barely early mid-life, so the presbyopia club is ever-expanding. We now think of presbyopia as middle-age vision and more and more people are entering that age range than ever before.

For pilots, presbyopia can be a huge pain, but one thats easily addressable with corrective lenses. Because pilots operate in a unique environment requiring near vision-for chart reading-mid-vision for instrument scanning and distance vision for traffic and navigation, the right kind of corrective lenses matter. A lot.

These days, most pilots opt for progressive addition multifocal lenses or PALs, a technology thats come a long way during the past decade. But progressives vary widely in their suitability for cockpit use. Heres a guide on how to select them.

Equipment Failure

So, why does the focusing mechanism fail in the first place? The The answer is that we slowly lose our ability to focus from the time we are born. Like a complex auto-focus camera, the human eye has a lens located directly behind the pupil, surrounded by a radial-shaped muscle called the ciliary body. The muscle is innervated by a complex of nerve connections between the brain, the pupil and the other eye.

When looking far away-beyond 20 feet-the lens is in a neutral position; no focusing is required. As the eyes look at objects closer than 20 feet, focusing becomes necessary; the closer the object, the greater the focusing requirement.

You can actually quantify the amount of focusing demand at a given distance. For example, at 16 inches (40 centimeters), +2.50 diopters of power is required. For you mathematics buffs, by definition, +1.00 diopter takes infinite (beyond 20 feet, or 6 meters) light and focuses it at 1 meter.At 30 centimeters, +3.00 is required; at 20 cm., +4.00 and so on. You can see how, as you get closer, the power requirement increases significantly.

At birth, the eye can focus as close as 2 cm, but as we age, this distance decreases. However, most of us don’t notice whats going on until it affects our lives, usually with difficulties reading normally. On one flight, you can read the minimums box on the plate, on the next you cant.

Why does all this happen? The crystalline lens, which does the focusing, becomes more sclerotic and hardens as we age. Thats because the most unique tissue in the body, the lens itself, is about 30 percent protein, where all our other tissues are almost completely made of water. Proteins denature with time, so the lens gets harder. Its not the muscle weakening. Its the lens stiffening.

Eye exercises wont help, by the way, so don’t waste your time and money on hocus-pocus schemes. This isn’t a muscle problem, its a lens problem. You cant make those poor muscles do any more than they already are. So, its either off to the eye doc or the AME, who then sends you to the eye doc. I personally recommend an eye exam before your medical, just to avoid raising the profile with your AME.

Now What?

There are several ways of dealing with presbyopia. They are eyeglasses, contact lenses, corneal refractive surgery-monovision Lasik or conductive keratoplasty or CK-surgical reversal of presbyopia and accommodating intra-ocular lenses, a form of cataract surgery, which the FAA just approved at press time. Corneal surgery is done monovision, meaning one eye is for far vision and one for near. It requires, for FAA approval, a six-month period of eyeglasses along with the monovision, followed by a waiver with a medical flight test. Monovision or bifocal contacts arent permitted by the FAA.

While still a point of intense debate, the FAA disallowed monovision contact lenses in the aftermath of the Delta Airlines Flight 554 crash at La Guardia Airport on October 19, 1996. The NTSB ruled that the probable cause of the crash was pilot error due to the inability of the captain to overcome misperception of the airplanes position on the visual portion of the approach because of his use of monovision contact lenses.

So, simply put, eyeglasses remain the best, simplest choice for pilots.Think of these glasses as nothing more than a tool to help you see what you need to see, when you need to see it. Keep in mind that by using these lenses, you don’t become addicted. The glasses don’t make your eyes get worse; they will continue to get worse whether you wear glasses or not.

Lens Choices

There are basically five options. They are single vision, lined bifocal, lined trifocal, blended and progressive. Single vision readers are fine for the computer or reading in bed because you can see clearly looking straight ahead at a single distance, usually 16 to 18 inches. But that wont work in the cockpit, because you need to see at a variety of distances and especially far away.

Bifocals are a better choice, since you can see near and far simultaneously. The downside is the slightly higher cost, the ugly line, which can get in the way, and range problems. Whats a range problem? Every lens has a focal power. So if the bifocal is set for 16 inches, you cant see at 24 inches and vice versa.

A younger presbyope wont have as much trouble with this as an older one will-say, 43 versus 53 years old-because the lens power is less in the earlier stages. But, eventually it will become an issue. And besides, who wants a line in their glasses anyway?

Trifocals solve the range problem, by providing distance, mid-range and near focal powers all in one lens. All of the advantages of the bifocal are there, plus a solution to the range issue. And thats great, except you now have not one, but two lines to deal with. The difference in price is minimal, but those lines…

Which brings us to the no-line category of lenses. There are two types of no-line lenses, blended and progressive. Blended lenses are purely cosmetic; they are no better than regular bifocals as far as range goes and in some ways, theyre worse. Imagine a lined bifocal, with the line rubbed out-thats a blended lens. So you not only have a lens with just two parts, but also a distorted area between those two parts. Which is exactly why we in the business call them the poor mans progressive.

Whats left is the progressive addition multifocal lens, or simply put, progressive. I like to compare the progressive lens to the Swiss Army knife.It does a little bit of everything, but it isn’t specific for just one task such as, say, a carving knife. A single-vision pair of computer glasses would be like that carving knife-perfect for the computer, but useless for much else.

The progressive lens has all the advantages of the trifocal, without any lines. we’ll over 50 percent of all multifocal lenses made in the U.S. are of the progressive design. It provides excellent vision at far, near and midrange, without the distracting line. Its by far the closest replacement to out-of-service zoom focus you can get, making it the best choice for pilots.

How They Work

Progressive lenses have been around, in one form or another, since 1959. They have evolved over the years through many generations. But one thing they all have in common is that they have a distance portion at the top-which may be no power at all, for you eagle eyes-with a progressively stronger corridor that increases as you look down, to provide for near focus. What this means is that you can see the approach chart through the lowest part of the lens and your gauges through the middle corridor. And when approach calls traffic, just look straight ahead through the upper portion of the lens. No need to be distracted by taking the glasses on and off.

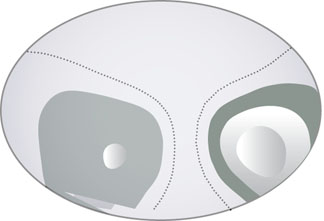

As depicted in the diagram, the lens design allows for unrestricted horizontal gaze in the distance, with a corridor for the middle ranges and a maximum power area at the bottom, usually set for 16 inches or so. As depicted in the diagram, the lens design allows for unrestricted horizontal gaze in the distance, with a corridor for the middle ranges and a maximum power area at the bottom, usually set for 16 inches or so. The transition between sections is seamless and smooth. But, this comes at a price. In order to make this transition continuous, there’s a compromise in the lateral vision in the middle corridor and near zone. We call these lateral limitations unwanted astigmatism and unwanted distortion. Looking through these areas, you wont see clearly.

Not until the late 1980s were progressive lens designs beginning to deal effectively with peripheral limitations in the near-vision portion of the lens. There are an infinite number of possibilities in these lens designs.The bottom line is to find ways to keep the unwanted astigmatism as far as possible away from the most commonly used parts of the lens. This profile can be illustrated by a contour plot, which shows the fingerprint of the specific lens design.

Each profile has pros and cons. Some designs work best for midrange (computers), while some allow for more near area vision. There’s no single best design and each manufacturer will claim that their product is better.However, its critical for the provider of your eyewear to be familiar with all the lens design options and their specific properties, especially when it comes to flying. I feel that distance area considerations are especially important in the cockpit. More on that in a bit.

PAL Type Ratings

So, how many progressive designs are there and which is best for you? My last count was about 28 contemporary designs. There are about six newer designs that I prefer. Thanks to computer modeling and patient trials, these most current lens designs are easier to wear, providing maximal fields of view and clarity of vision.

Distance viewing area is a major consideration for flying, especially for those who never needed glasses until age 40. Distance areas range from 18 mm2 to 56 mm2. Thats a lot of variation. Intermediate is second in importance, in my view, because thats for the instruments over to the transponder and radio/GPS stack. Intermediate areas in the mid-strength prescriptions range from 13 to 28 mm2. Unfortunately, the lenses with the most intermediate area are not the same as the ones with the most distance area. And that, folks, is why there is no single best choice.

At the end of the day, a number of variables need to be considered to arrive at the right choice for cockpit use. These include the cockpit configuration, frame preference and prescription. To make it more complicated, there are lens materials and treatment choices. You have your pick of materials such as glass, plastic and polycarbonate. Lens extras include high index and anti-reflective, transitions (for plastic) and polarized, scratch-resistant and photochromic for glass.

My personal preference is plastic lenses with an anti-reflective coating such as your quality camera lens has. Glass lenses are just too heavy. I also prefer polarized lenses for daytime flying, although I am just a piston driver. You should know these don’t work very we’ll with tempered windows and with some avionics displays. I learned this the hard way in a King Air. I ended up having to use my clear glasses to see. So you Plexiglas window folks can use polarized- not so for the heavy metal crowd.

Fitting Considerations

Its critical to look through the central portion of these lenses. A quick look at the contour plot/fitting cross diagram on page 16 will help. I suggest, if possible, superimposing the fitting cross on a contour plot of the lens you have in mind to show how important this really is.

Its all too easy to make an error in proper lens placement; if the center of the lens doesnt align with your pupil, you will be looking through distortion areas instead of seeing clearly through the corridor of clear vision. Since you cant see the marking in the lens used to make this alignment, you must have confidence that the optical professional doing the fitting is experienced.

At one time not so long ago it was common for patients to have trouble adjusting to PALs. But the good news, according to Dr. Bob Lee, clinical professor at the Southern California College of Optometry, recent studies have shown that success rates for progressives are as high as 98 percent.And the chief causes of non-adapting are measurement error, followed by lack of proper instruction and failure to properly troubleshoot problems through frame adjustment.

So, no quitters allowed. PALs sometimes require an adaptation period as a long as a week. Occasionally, they have to be re-made, either because of a prescription or measurement problem, a fabrication error or even because you need a different style of lens than was anticipated. Be patient. Also, the frames need to be adjusted periodically. Your eye-care provider should offer this service at no charge. Speak up if there are any difficulties. Odds of success are far better than they ever were.

Buying Recommendations

First, find an optometrist familiar both with progressive lenses and aviation. How? Ask your hangar buddies for a recommendation but also check this Web site for a listing of aviation-savvy professionals: http://209.83.210.5/drlocator/search.asp. Second, use an optical dispenser that knows its stuff and will guarantee its work. Usually, that will be in the same place as the optometrist, but not always. I have a dispensary with more than 1800 frames, four opticians and my own in-house lab. Bigger is not always better, but it helps. A dispensary with an in-house lab is helpful, because they can give a quicker turnaround and if there’s a problem, they can do it again just as quickly.

don’t try to find the cheap way out. Better quality lenses work better.But they cost more. You wouldnt use the cheapest headset (who needs the headache?) and you don’t want inferior quality frames or lenses, either.Stick to the name brands.

don’t give up. Work with your eye doctor and optician to find the best solution for your needs. Remember, there is no best answer; the solution for you is the one that works for you. The sidebar on page 16 gives my specific recommendations for lens brands. Others may certainly do just as we’ll but Ive had consistently good results with those listed.

A word about frames: Until recently, there were significant limitations on the vertical dimension of the frame. We needed at least 21 mm between the pupil of the eye and the bottom of the frame. Now, with recent advances, we can accommodate as little as 14 mm. That means that smaller, cooler looking, more comfortable frames are fine for PALs. And unlike days gone by, frameless and drill-mount designs of lightweight titanium can be used for progressives.

Im partial to titanium mountings; theyre durable, hold their shape, can be bent and sat upon (not recommended) and still remain light. And I always recommend the smallest frame size that will work with your face and prescription. For sunglasses, I recommend a frame large enough to protect, but with a minimal wrap. The Terminator look is cool, but the distortion in a prescription lens is not going to make you smile.

Also With This Article

“PALs: Getting the Fit Right”

“Multi-Focus IOLs Get FAA Approval”

-Dr. Bob Glass practices optometry in Costa Mesa, California. He owns a Piper Warrior.