You can hardly blame the owner of a Lycoming-powered Cessna or New Piper aircraft from recoiling in dread at the thought of opening the mail. By now, hundreds have been on the receiving end of urgent airworthiness directives grounding their expensive airplanes because of faulty crankshafts.

In one of the most far-reaching aviation recall fiascos the industry has seen, many owners have been told that their expensive airplanes-some of which just emerged from the factory-wont be flyable until March or April of 2003 as the FAA scrutinizes and recertifies how Lycoming builds crankshafts. As we go to press in late October, Lycoming was expecting forging of crankshafts to begin in November, with finished cranks available early in 2002.

Although Lycoming has attempted to mollify owners by paying carrying costs for beached airplanes and reimbursing rental costs, owners weve interviewed are understandably hopping mad and the stench is rubbing off on both New Piper and Cessna.

There’s no way, under any circumstances, that Id ever buy a new airplane from New Piper Aircraft again. No way at all, says Don Werlinger, a Houston pilot whose 2000 model Saratoga II-TC has been grounded twice for crankshaft problems and wont fly again until late winter.

Lycoming was already being sued by a number of New Piper Mirage owners over engine issues and now the crankshaft mess appears to be touching off more lawsuits that Lycoming may be defending for years to come. A class- action suit filed by Mirage owners accuses Lycoming and New Piper of deceptive trade practice and claims that Lycoming delivered engines which fell woefully short of durability and reliability claims touted in the sales literature. Worse yet, Lycoming is to be shortly sued yet again in a wrongful death action related to the fatal crash of a New Piper Mirage on August 4th of 2002, again apparently caused by an engine failure.

Obviously, many current Lycoming owners-and what may be a shrinking pool or would-be owners-are rightfully asking just what went wrong here. Whats Lycoming doing to straighten it out and how will the company prevent a recurrence?

We think these are fair questions and owners have a right to answers. However, when we approached Lycoming for its side of the story, meaningful information was scarce from the company. It took weeks and many calls to Lycoming and we still havent been told exactly what went wrong and why, a level of non-responsiveness that owners have bitterly complained about.

The History

Lycomings crank troubles first came to light last February when the company announced that some 400 turbocharged TIO and LTIO-540 300 HP-plus engines would be recalled in the wake of at least four crankshaft failures. Two of these were in new Cessna T206H aircraft but other models grounded included New Piper Mirages, Saratogas and older Lances and Navajos. Lycoming said it had no means to field check these crankshafts so the engines were shipped back to the companys Williamsport, Pennsylvania plant for inspection and replacement under service bulletin 550.

At the time, some industry insiders worried that Lycomings crankshaft woes would start out small and blossom into a major recall affecting hundreds if not thousands of engines, as had been the case when Teledyne Continental suffered its own crank crisis in 1999 and 2000. They were right.

In an August 16, 2002 service bulletin (SB552, which superseded SB550), Lycoming admitted to more field reports of broken crankshafts in six-cylinder turbocharged engines rated at 300 horsepower or more. This bulletin, which morphed into an emergency AD, followed close on the heels of a Malibu crash at Benton Harbor, Michigan on August 4th in which three people died. In this second bulletin, Lycoming again said the problem is related to the material used in the crankshafts.

Lycoming called for the immediate grounding of aircraft equipped with these engines and again told owners there was no available field test to determine if any of the crankshafts met Lycomings own specifications. Altogether, about 1800 aircraft were affected, some with new engines or overhauls dating back to 1997.

What most galled some owners is that they were nailed by both service bulletins and many still wont be flying for months.

On September 16th, Lycoming released yet another service bulletin (SB553) calling for the inspection of more crankshafts in new engines. But this time, the company had developed a method to evaluate the crankshaft based on core samples taken from the prop flange. Once again, the company released a long list of serial numbers describing affected engines. (Why Lycoming took so long to develop a field test procedure, as Continental had done with its crankshaft recalls, is unclear.)

Two weeks later, on September 30th, in a development related to the crankshaft mess only by dint of what is, in our estimation, continuing poor quality control, Lycoming recalled a batch of crankshaft gear retaining bolts installed from 1996 to 1998 (SB554). Again the issue is substandard metallurgy and again, owners are holding their collective breath hoping this bulletin doesnt spread like a virus, affecting every recent engine Lycoming has built.

Where It Went Wrong

As seems to be characteristic of aircraft companies facing a product crisis, Lycoming has been unforthcoming about exactly how and why the crankshaft crisis developed. Owners hit by both service bulletins say Lycoming has done a better job of informing owners the second time around than the first but none we spoke to considered themselves we’ll informed by the company.

To Lycomings credit, in late September, Lycomings president, Mike Wolf and chief engineer Rick Moffett spoke to the Malibu/Mirage Owners and Pilots Association convention in Tucson, Arizona and gave what members described as a forthright explanation of how Lycoming let the bad crankshafts slip through its quality control. We had hoped to see this presentation for ourselves but, as weve noted, we had difficulty obtaining any meaningful information from Lycoming. When CEO Mike Wolf finally agreed to an interview, we werent given detailed answers to our technical questions.

However, from our interviews with M/MOPA members who attended Lycomings presentation in Tucson and our interview with Wolf, we have pieced together a general history of the crank crisis.

Lycoming apparently first became aware of potential crankshaft problems shortly before SB550 was issued in February of 2002, after several reports of broken cranks in high horsepower engines surfaced.

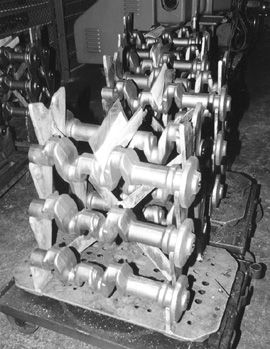

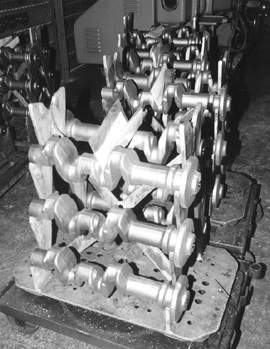

An investigation of broken cranks revealed that during the hammer forging process used to make the crankshaft blanks, the crank material was apparently overheated, causing brittle inclusions called honeycomb clusters.

These are subsurface defects not detectable by any kind of inspection, according to Lycoming. Although such defects may be uniform throughout the forging, Lycoming told the Malibu group that all of the bad crankshafts experienced fatigue failure between the number 5 and 6 journals.

Lycoming responded to these incidents by reviewing its quality control records in an effort to define a range of engine serial numbers that might be affected by the problem cranks. This was the basis of SB550. A second bulletin, SB552, following the fatal Malibu crash in Benton Harbor, expanded that serial number range to include some 1800 engines. When Lycoming learned of a crankshaft failure outside the range of the expanded serial numbers, it issued SB553, which allowed assessment of crankshaft metallurgy based on core samples from the prop flange.

Lycoming told the M/MOPA group that it has a good understanding of how many cranks are potentially bad. But some owners arent convinced. In the opinion of one owner we spoke to, the prop-flange exercise was a witch hunt that only served to inconvenience and stir doubt among owners.

So much for what happened. The larger question is why. And where was the FAA in this process?

Lycoming Responds

Lycoming has always forged its crankshaft billets and that work has always been done by an outsourced company. We are not a forging house, says Lycomings Mike Wolf. Yet it appears that broken cranks are a recent problem, extending back on a few years. What changed?

Were still trying to understand that. Obviously, its not something we know all the answers on. But because its under investigation, Id rather not comment, Wolf said.

Lycomings forging vendor was Interstate Forging in Navasota, Texas. Wolf declined to identify who the new forging house will be. FAA spokesman Paul Takemoto told us Interstate wouldnt be the vendor but Wolf told us Lycoming would be changing the forging process but using the same company. We take that to mean that Interstate will be doing the forging.

It will be a vastly different process. It will look the same but we have additional testing, such as a metallurgical test and an analysis to be able to assure ourselves that it will be done to specifications, Wolf told us.

Each crank will be forged with an additional attached piece called a prolong that will accompany the part through production. In addition to multiple lab tests, the prolong will also be subjected to a Charpy test, a standard metal test for impact toughness. Its not clear why a Charpy test wasnt being done before but Wolf said Lycoming had never done this as a standard practice.

Wolf told us forging under the new process would begin sometime in November but that finished crankshafts wouldnt be available for at least two to two-and-a-half months. Additional steps such as straightening, nitriding and, presumably, more inspections, extend production time.

If we can squeeze the time down-not at the risk of safety, of course, safety is still the most important thing-well do that. Im afraid to commit to anything shorter than two-and-a-half months, Wolf told us.

Once the crankshafts are flowing, says Wolf, the bottleneck will be assembling the engines. The company has lined up some 30 facilities worldwide to increase engine production to as much as 20 to 30 engines per day. Additional quality control stations will be in place at the Williamsport factory.

As for FAA oversight, were sure the plant will be crawling with inspectors. The more pressing question, in our view, is where were they before this happened.

Those are questions were asking ourselves, says the FAAs Paul Takemoto. He says that the FAA did respond by issuing emergency ADs based on SB550 and SB552. On the other hand, those ADs were issued post failure, after broken cranks had already revealed that Lycoming had quality control shortcomings.

As part of the FAAs production type certificate process, some means of effective quality control must be in place at companies which manufacture certified engines and airframes. If the FAA had an oversight role here, it obviously wasnt effective.

See You In Court

With neither the FAA nor Lycoming clearly explaining why the QC process failed-if they even know-the most meaningful answers may emerge in another venue: a U.S. district court.

Even before the most recent round of crankshaft recalls, Lycoming and New Piper were the target of a class-action suit pursued on behalf of Malibu Mirage owners by the Dallas-based Fred Misko law firm. Although a U.S. district court in Florida disallowed the Mirage owners class status in September, Miskos Charles Ames told us that this decision will be appealed and the case will, in any event, be pursued by the lead plaintiff, Mirage owner William S. Montgomery.

In a luxury not often seen in even major lawsuits, the Montgomery claim has its own Web site: www.textronenginelitigation.com.

Even more surprising is that summaries of the major depositions are posted for all to see, although the full text is reserved for Malibu owners and class members. Interestingly, although many aviation lawsuits seek damages for wrongful death or personal injury, the Montgomery suit offers a novel approach: the complaint centers on deceptive trade practices and false advertising, a claim that might be difficult to prove.

The suit argues that in its sales literature, New Piper and Lycoming made claims for the airframe and powerplant that werent supportable. Piper, for example, claimed the aircraft was safe and reliable while Lycoming said the Mirages 350-HP TSIO-540-AE2A had a 2000-hour TBO.

The Mirages safety record might be arguable but for years, owners have complained about chronic engine problems, high maintenance incidence and TBOs we’ll short of the 2000-hour claim. According to Aviation Consumers owner surveys and reporting, top overhauls and other major repairs are common before mid-time.

The Montgomery suit claims that when Lycoming began aggressively outsourcing components such as crankshafts, valve train parts and cylinders beginning in the early 1990s, its quality control went downhill. The filing says that in 1994, five years into Lycomings outsourcing efforts, it sold off key quality control equipment and reduced the number and level of in-house quality control inspections, relying on inspections at the outsourced vendor end of the supply chain. In one eye-opening deposition, Donald Kleese, a former crankshaft inspector at Lycomings Williamsport plant, said the joke around the plant was if the outsource could not be made to conform to the blueprint, then they would change the blueprint. Lycomings Wolf declined to comment specifically on the lawsuit, other than to note that its in progress and that many of the claims are just information put out by plaintiffs attorneys thats untrue or misunderstood.

Keep in mind that this suit was filed before the crankshaft issue emerged but the investigation leading up to the filing highlighted another TSIO-540AE2A problem: premature bearing wear. It appears that the bearing wear and metallurgical problems with crankshafts are unrelated. In depositions, Lycoming confirmed that the bearing loads in the Mirage engine are among the highest of any of the companys products.

According to the lawsuit claims, Lycoming and New Piper were warned as early as 1997 that premature bearing wear could cause engine failures in the Mirage. According to the filing, Lycoming had 14 reports of bearing problems in Mirages in 1996 and 1997. Yet the suit contends that Lycoming took no action on this problem until May 2000, when it warned owners to check for metal particles in the oil suction screen and recommended discretionary bearing replacement. In August 2000, Lycoming made the bearing replacement mandatory and it also called for a mandatory oil and filter change every 10 hours until the bearings were replaced.

The Misko firms Charles Ames told us that a second lawsuit involving crank quality control issues is being considered but the firm hasnt decided when it will be filed or if it will be a class-action suit or individual suits. Ames told us distressed Lycoming owners are popping up almost hourly.

Company Assistance

By late October, Lycoming said that its response in helping customers through the crank crisis was unprecedented and we cant argue that claim. In a Lycoming-funded assistance program totaling at least $37 million, owners are being given a choice of reimbursement of aircraft carrying costs-hangarage, interest on loans and AOG insurance or reimbursement for travel expenses, including commercial air fare, rental cars and even rental or lease of an equivalent aircraft. One owner told us that Lycoming is paying $2500 a month for a dry lease he negotiated on a new Cessna 172.

To sweeten the deal, Lycoming is offering a supplemental payment-$100 a week for one 206 owner we spoke to. But there’s a catch: if you accept that deal, you have to agree not to sue Lycoming over loss of use of the aircraft.

If this sounds like buying off customers, were sure it will be viewed that way by many. On the other hand, from Lycomings view, paying off customers ahead of time probably makes good business sense. Its not only a fence mender but likely to be cheaper than defending dozens of lawsuits or paying out settlements.

What Owners Say

Were not surprised that attorney Ames is hearing from many angry owners. For this report, we interviewed or e-mailed a dozen Cessna and Piper owners whose mood we would describe as ranging from boiling mad to surprisingly tolerant. Although a couple of owners told us they were considering legal action against Lycoming to recover losses, we sense that most of these owners would like to stay out of court.

Most of these guys are business people and entrepreneurs, said one owner, and theyre smart enough to know that suing anyone is going to be an expensive waste of time. But the public relations damage may be devastating and long lasting. New Piper may get the worst of it.

Houston-based Don Werlinger, whose 2000 Saratoga II-TC has been beached twice in one year for crankshaft problems, says he has had it with New Piper. Although he thinks the company did better by him the second time around than the first, hes unhappy that New Piper hasnt done more to intercede on his behalf.

If I own a Ford and the intercooler goes bad, the dealership doesnt send me to the company that made the part. They step up and take care of it, Werlinger told us. For that reason, he wont buy another New Piper. What about other New Piper owners?

It depends on how we get through this, says Barry Howe, a Boston-area Saratoga owner. Hes also reluctant to seek a legal remedy but faults New Piper for not being more aggressive in helping its grounded customers. I think [New Piper CEO] Chuck Suma needs to show some leadership and get some information out there, Howe says.

New Piper spokesman Mark Miller told us the company is contacting owners and keeping them abreast of Lycomings offer. But, he says, its a Lycoming program, not a New Piper program. New Piper will extend the warranties of aircraft owners grounded by the recall.

Understandably, few of the owners we talked to accept the notion that faulty crankshafts go with the territory when you own an airplane. Its unbelievable to me that this could be allowed to happen, says Mike Sahm, whose 2000 Mirage was also grounded twice for crankshaft replacement.

Ironically, Sahms business makes machine tools used in automotive crankshaft manufacture so he understands the technical issues intimately. He says that with modern forging and machining techniques and statistical process control, quality lapses of the magnitude that have bedeviled Lycoming shouldnt happen.

Judging by comments weve heard from readers, none of the companies involved in the crankshaft fiasco have won the undying gratitude of owners. Lycoming was uniformly faulted for poor communication and lack of response.

Cessna deserves some credit for aggressively contacting its customers to explain Lycomings financial aid package, even if Lycoming didnt distribute this information effectively. But that doesnt mean owners are satisfied or happy.

How can you be satisfied? asks Aviation Consumer contributor Lionel Lavenue, whose Cessna 206 is grounded by the crank recall. Ive come to the realization that there’s absolutely nothing I can do.

Conclusion

To give credit where its due, we applaud Lycoming for stepping up and supporting customers with financial aid. The program the company is offering is fair almost to the point of being generous.

But in our view, that doesnt offset the considerable damage the company has done to its reputation for having allowed the substandard crankshafts to slip by in the first place. Itll take more than financial assistance and a clever ad agency to fix this mess.

In our interviews with owners, we were frequently asked if Lycoming will survive its crankshaft crisis. Although our crystal ball is no clearer than yours, we think it will. Lycoming is a tiny division of Textrons giant $12-billion empire and although it accounts for a mere pittance of that total, aircraft sales in general-mostly Cessna jets-is Textrons largest business segment. Were sure the company will survive.

Clearly, Lycoming had significant quality-control lapses, although just where and why they occurred remains unresolved in owners eyes. The company reached out to the Malibu community to explain both the QC lapses and the fixes to prevent them recurring. But in our estimation it has done a mediocre job of communicating the particulars to buyers sophisticated enough to understand the technical issues and who are naturally suspicious when theyre kept in the dark.

The overwhelming sentiment among owners is that Lycoming could have saved both itself and owners untold grief by investing a fraction of the total it will spend on remediation in adequate quality control in the first place.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Checklist.”

Click here to view “How Do The Car Guys Do It?”