Back in the day, the quest to come up with the perfect personal airplane may have seamed easy at first. It only needed to perfectly combine ease and cost of operation, ability to carry the right number of passengers and operate from most all airports in the country.

During the post-World War II boom, the major airplane manufacturers to include Aeronca, Luscombe, ERCO, Piper and Cessna, among others, all eventually came to the conclusion that the future for mass-marketing airplanes was wrapped up in something that had four seats and on the order of 150 HP. ERCO (the Ercoupe folks) never made it past a prototype. Aeronca and Luscombe gave up after limited success, while Cessna and Piper went on to fight it out for decades, while Beech and Grumman-American tried to make inroads.

That niche proved to be the beginning rung of a market ladder where airplanes can excel as trainers, but can also be practical traveling tools. The tradeoff is they won’t haul a lot of people or cargo, nor will they do it quickly, but they offer economical travel. They often serve as a pilot’s first “real” airplane after primary training. The market demands that they be reliable, inexpensive to operate and relatively easy to fly. They must excel as rental airplanes—thus be designed to be flown by any pilot, and withstand the consequent beating, while providing a reasonable income to the FBO.

Cessna won that war—the Skyhawk ended up owning that market, and used-airplane prices reflect that dominance, but the Piper PA-28-151 or -161 Warrior came a respectable second. It, and the AGAC AA-5 Traveler/Cheetah, are good, solid airplanes that can be had for less. (Beech’s entry, the Sport, is short on performance when compared to the Warrior and Cheetah.)

The AA-5 went the way of the dodo in the late 1970s, and attempts to resurrect it (in the form of the Tiger) failed. Beginning in the mid-1980s, Piper, too, fell on hard times and was forced into bankruptcy, finally emerging several years (and a few abortive buyout attempts) later as the New Piper. In 2006, “new” was dropped from the company’s name. Today, all seems good at Piper.

Unlike the Skyhawk, and with only one or two exceptions, the Warrior has been in production throughout, even if the number of airframes manufactured in the last several model years could be counted on the fingers of one hand. In the “Warrior III” configuration, the model was marketed mainly as a trainer before quietly disappearing from Piper’s lineup a few years ago. But, along with other trainers—including the twin-engine Seminole and the complex Arrow—the Warrior is back in the lineup again. In its marketing, Piper says the Warrior has been a flight school favorite since its inception. Equipped with a Garmin G500, plus a GTN650 touchscreen avionics suite, ADS-B system and other modern electronics, the new Warrior sports a price tag nearing $300,000. Late last year, Flight Safety International took delivery of 20 new Warriors.

A glance at current prices of mid-1980s Skyhawks and Warriors shows that PA-28-151/161 prices have closed some of the historical gap with the Skyhawk, but are still a relative bargain: The 1984 Cessna 172P II averages $10,000 more than a 1984 Piper Warrior (which averages $35,000 retail), according to the Aircraft Bluebook.

History/Performance

As general aviation was entering its heyday of the 1970s, Piper’s line was beginning to look dated. The basic PA-28 had come out in 1962, and hadn’t changed all that much. Piper’s PA-28 and -32 singles all had the characteristic, constant-chord “Hershey bar” wing, and the company was about to lower the boom on the sleek Comanche. It was time to update the line.

A new airplane was planned, one that would take aim squarely at the Skyhawk. Previously, Piper didn’t really have a strong competitor for the Cessna 172, even though it offered Cherokees with 150 or 160 horses through most of the 1960s. The Cherokee 140 was more cramped, being more of a 2+2 airplane than a true four-place, and it didn’t perform as we’ll as the Skyhawk.

The first Warrior was introduced in 1974, powered by a 150-HP Lycoming O-320-E3D engine. It didn’t replace the Cherokee 140, though the 140 did succumb to poor sales after the 1977 model year.

The Warrior boasted one big difference: a new, longer, semi-tapered wing with a higher aspect ratio. This new wing helped the handling, with lighter roll control forces, and also boosted the climb rate. It also helped the airplane’s looks. The new wing design first appeared on the Warrior, but eventually found its way into all of the PA-28 series as we’ll as onto the PA-32.

Interestingly, the new design represented a deviation from the production efficiencies originally touted as a virtue of the constant-chord wing. And it’s fun to recall some Piper engineers, back when it was introduced, boasting that the fat, new, stubby wing was actually every bit as good as the sexier-looking tapered Comanche wing, aerodynamically. Piper’s most significant upgrade to the Warrior came in 1977 when a slightly different O-320 engine—the -D3G—was bolted on, offering a 10-HP boost in output. The results were dubbed “Warrior II.”

A couple of other evolutionary changes occurred in 1978, when Warriors received more streamlined wheel fairings, and in 1983, when the battery was removed from under the rear seat and placed in front of the firewall. The new fairings—aftermarket versions of which are available under STC—yielded some 7 knots in cruise speed, according to the book (optimistic numbers, users tell us), while the battery change shortened the run to the starter and helped combat starting problems (though these had been largely overcome, according to users, by swapping copper for aluminum cables).

Thanks to the change in weight and balance, shifting the battery location allowed the gross weight and useful load to be hiked by 115 pounds, and extended the aft CG to allow more of a load in the baggage compartment. (The boost is available via STC for older Warriors.)

An attempt to create some interest in a moribund new-airplane market was made in 1988, when Piper released a version of the Warrior, targeting flight schools, called the Cadet. A stripped-down Warrior, it was available in VFR and IFR versions. The experiment continued through the 1994 model year. Another spruce-up resulted in the Warrior III in 1995, which remained in production through 2012.

Today, a 2012 Warrior III with standard equipment will set you back $289,900, while an average 1974 model brings about $25,000.

The 10-HP boost in power raised the published 75-percent cruise speed from 116 knots to 121 knots. And the new speed fairings nudged that up to a claimed 127 knots—not exactly blinding, but squarely in league with the Skyhawk, even if easily eclipsed by the Cheetah. Owners told us in no uncertain terms that real-world performance is we’ll less than the book figures: Owners of the 160-HP model reported cruise speeds from 110 to 120 knots. On the good side, the fuel burn at 100 knots can be as low as 8 GPH.

One big gripe by owners of the 150-HP model is a miserable climb rate. “It’s taken me to 292 airports in 35 states. As a Jack of all Trades (master of none), it does not climb rapidly, carry a lot of weight or go fast,” wrote one owner of a 150-HP model.

One of the nice features is a generous 50-gallon fuel load (with 48 gallons usable). Burning 7.5 to 10 GPH at cruise, these birds yield a fairly good range with four to six hours of flying. One pilot said he flight planned for 4.5 hours with a 45-minute reserve, and one appreciated the endurance when IFR.

Another owner wasn’t happy, saying, “There are times when 50 gallons has been limiting, and I would have liked to have had at least 72 gallons, as did some of the Arrows.”

Runway performance is adequate, with an owner of a 160-HP model reporting his being flown from a grass runway. He says the airplane is “adequate for the 2600-foot strip. I’m careful with four passengers on high density altitude days,” however, especially if the grass hasn’t been mowed.

Comfort/Loading

While past respondents rated comfort only as average, the current consensus is it’s quite good. Later Pipers benefit from having some of the best seats in general aviation, from both a comfort and crashworthiness standpoint. These seats are designed with an S-tube frame similar to the legendary JAARS seat, which progressively deforms during impact, absorbing energy before it reaches the occupant. For greater pilot comfort, there is an optional vertical seat adjustment which some say is great, but others say is prone to malfunctioning.

The fuel selector is located out of sight alongside the pilot’s left knee. The need to switch tanks left and right results in more fuel mismanagement accidents than with the “both tanks” system on the high-wing Cessnas, judging from the accident reports. Naturally, it’s also easy to develop an imbalance unless the pilot remembers to switch regularly, and there is no aileron trim for the airplane. This makes at least a wing-leveler autopilot a nice option, in our opinion.

The Warrior’s parking brake is a robust handle sticking out from the bottom of the panel. It’s simple and strong, and it works. The same goes for the flap system. It’s manual, positive, blessedly simple and it just doesn’t break.

Like most low-wing aircraft, however, entry and exit is awkward. The Warrior has only one door, so three of the four occupants have to do some contortions to get in place. Emergency egress is problematical, since the rear windows cannot be opened in an emergency (like those of some Bonanzas, for example). The baggage door is fairly large, however.

Naturally, with a full load of 50 gallons, the Warrior won’t carry four adults, but some owners report fuelling up only to the tabs (34 gallons), accepting the reduced range and legally flying off to their destination. The baggage compartment will take a full 200 pounds structurally, the same as more powerful PA-28s. That’s a lot more than the Skyhawk and Cheetah’s maximum of 120 pounds, by comparison.

Most owners say nice things about cabin ventilation, thanks to an abundance of outlets, both overhead and underneath. Unfortunately, there were complaints that in winter the overhead vents were too much of a good thing and could not be completely shut off, giving passengers the chills. Pilots have solved this problem by simply taping up the exterior air inlet on the tail in the winter. We also received reports of the heater baking the ankles of those in front while rear passengers froze.

A few owners had the air conditioning systems available as options on the Cherokee line. Those who did felt the cool air yield in summer was not worth the sacrifice in already-limited payload and performance.

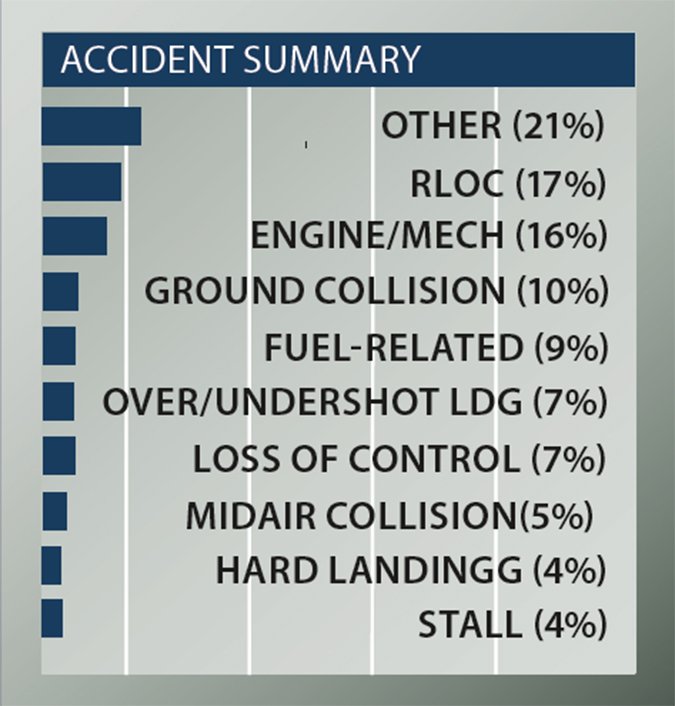

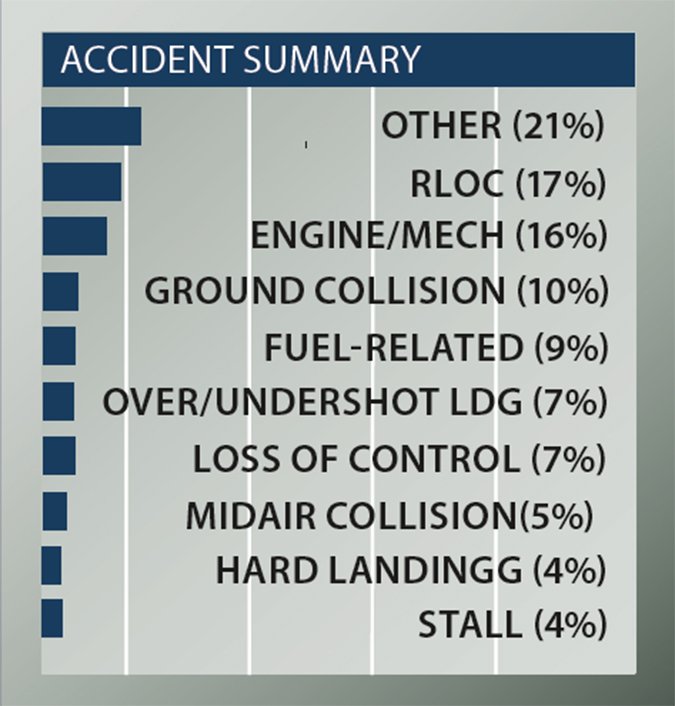

PA28-161 Wrecks: Other and RLOC

As might be expected of a Swiss Army Knife airplane—the fact that the Warrior is used for virtually all types of general aviation operations other than crop dusting—our search of the most recent 100 accidents turned up every sort we could imagine and some we couldn’t.

As we looked at Warrior accidents from the perspective of potential design issues, we saw two areas that got our attention. On the favorable design side, there were 19 runway loss of control (RLOC) accidents—a number we consider low. To make the number even more attractive, only five of the RLOC events involved certificated pilots; the other 14 were students. Overall, we think the ground handling of the Warrior is excellent.

On the negative design side, the fuel system breaks the available fuel into two packages. The pilot has to keep track of where the fuel is and select the appropriate tank—which means there will be mistakes. There were nine fuel-related accidents, four of which involved not positioning the fuel selector appropriately. Pilots with 12 and 17 gallons remaining in one tank put the airplane on the ground after running the other one dry. One pilot turned the fuel selector to the “off” position when changing tanks and another evidently couldn’t decide which tank he wanted as he pointed the selector to a spot between the “left” and “right” positions. Five pilots were able to use all the fuel in the airplane before landing in the boonies.

While a left/right/off fuel system is common, it is more prone to fuel-related mishaps than a system where the pilot does not have to switch tanks during a flight and should be treated with respect.

There were 10 on-ground accidents—a puzzlingly high number. Nine involved Warrior pilots who taxied into posts, signs or other airplanes. We can’t explain such a high rate—the wings aren’t inordinately long, it has good visibility and we like the way the airplane handles on the ground. We felt sorry for the Warrior pilot who was minding his own business—doing his runup—when another airplane taxied into him.

Of the 17 inflight engine power loss events, five were due to improper or lack of maintenance. That investigators couldn’t determine the cause of the remaining 12 didn’t give us any warm fuzzies.

There were two deer strikes, something we’ve noticed has become common in the last 10 years. There were five midair collisions—a surprisingly high number. We expect to see not more than one or two. Of them, two involved instrument students under the hood in airspace used for intensive student training.

With its modest power, we were not surprised to see a number of Warrior accidents involving takeoffs or go-arounds from short runways, especially when loaded at or above gross. All of the stall accidents were on initial climbout from a short field or a late go-around. Others hit obstructions after takeoff or after aborting a takeoff when they decided they couldn’t make it. Often the POH numbers made it clear the proposed takeoff was impossible so we weren’t terribly compassionate toward pilots who survived those events and later said they couldn’t understand why the airplane didn’t seem to accelerate or climb.

Handling/Competition

The Warrior shares with the other Cherokees a gentle nature, pleasant handling and such a reluctance to stall aggressively that some pilots rate it a poor teacher. Several respondents said that with both rudder and stabilator trim, the airplane does not need an autopilot.

We’d rate runway handling as good, despite the number of accidents on both takeoff and landing—especially landing—we uncovered in past checks of FAA accident and incident reports. Further investigation revealed that many were student training accidents.

Pilots report they like the way the aircraft handles in a crosswind landing and feel more secure taxiing in windy conditions with the wide gear stance, as opposed to operating in the high-wing Cessnas.

The Cessna Skyhawk and the AGAC Traveler/Cheetah are the most logical competitors to the Warrior for the attention of buyers who want four-seaters that won’t break the bank and who are willing to settle for modest performance.

The Cessna has by far the best overall safety record. In a cross-country race, the Cheetah would edge out a 160-HP Warrior with the later wheelpants (the Traveler is slower), and leave the Cessna and the older Warriors in its propwash. And while the Traveler/Cheetah has the most pleasant, facile handling, in our book, it is not as adept at handling short fields. The Cessna gets our nod for getting in and out of little runways.

Maintenance

Here’s where the Warrior should shine, since it’s the opposite of high-tech sophistication. It’s got fixed gear, a fixed-pitch prop, mechanical flaps and a small-bore carbureted engine. It also comes with a cowling providing the best engine access in its class: Doors on either side of the cowling are hinged at the top and secured with double latches. By contrast, gaining similar access to a Skyhawk’s engine requires removing several screws and then lifting off the cowling’s upper half, a two-person job when done correctly.

As expected, owners report relatively low maintenance costs and modest annual inspection fees. But it’s a good thing they have that cowling: The engine compartment is the source of most upkeep problems. Our checks of Service Difficulty Reports (SDRs) showed a host of problems with carburetors and a number of magneto failures. The powerplant itself was tagged with several failure modes, valves being at the top of the list, followed by camshaft/lifter/pushrod problems, cylinder cracks and rocker arm breakage.

Potential buyers should check to see if there is roughness following engine start, since according to Lycoming that’s one sign the exhaust valves are beginning to stick. (The roughness usually goes away after the engine warms up, incidentally.)

High-time Warriors usually got that way as a result of being in a training environment. As one result, landing gear components and attach points, along with their fasteners, are subject to numerous cracks and corrosion.

If you’re looking at a Warrior equipped with air conditioning, take a look at the bracket that attaches the alternator and compressor. We noted reports that the mounting bolts had broken or worked loose. And in one case the submitter found the bracket was installed backward, subjecting the rear tab of the alternator to stress and misalignment of the pulleys.

0)]

Mods/User Groups

One series of mods available from Plane Dynamix for earlier PA-28 models also can be installed on Warriors. These include a set of vortex generators, modifications to the standard Sensenich prop blade designed to reduce drag, a new, more-efficient cowling and—for -151 Warriors—an upgrade to 160 HP. We have no direct information on these mods’ effectiveness, but Art Mattson (who recently sold the company to Plane Dynamix) has regularly set speed records in his Cherokee 140.

Owners of 1977 through 1982 Warrior IIs can get a gross weight increase, from 2325 up to a whopping 2440 pounds. Mostly a paperwork exercise requiring a placard and carrying a later Piper information manual, the STC gives early -161 owners the same gross weight 1983 and later models enjoy. Ventura Aero offers this mod.

Another interesting STC involves installing a supplemental storage area under the baggage compartment floor, capable of storing up to 25 pounds. The mod, available from Aircrafters Inc., includes parts and paperwork for the conversion.

Other mods include ones from LoPresti Speed Merchants, Met-Co-Aire and Knots 2U. This includes gap seals and new wingtips—including tips with landing/recognition lights.

As with any personal airplane, we strongly recommend joining its type club. The expertise can save real money when tracking down common parts and problems. Warrior owners are fortunate in that they have an excellent organization, the Piper Owner Society, which merged with the Cherokee Pilot’s Association. There is also a Piper Forum where Piper pilots exchange thoughts.

Owner Comments

I have a 1974 Warrior. This is the first year for the PA28-151. It is basically a PA28-140 with a 5-inch stretched fuselage and tapered wingtips. It uses the bulletproof Lycoming O-320 engine. The Cherokee 140 line of aircraft are pretty much used for training, up through the IFR rating. It is not stellar in performance by any means, but does fit the need for quite a few private owners—me included.

My Warrior has a pilot seat that is vertically adjustable and has a gas spring to smooth out the bumps. The poor instructor or passenger has to deal with a non-vertical-adjustable seat. There is a bench type seat in the rear. I don’t know of any Warriors that have individual bucket type seats in the rear. The Piper Archer is almost identical to the Warrior. The major difference is the Archer has the Lycoming 0-360 engine, instead of the lower-powered O-320. But, the O-320 serves my needs, for the most part. I can trip-plan for a 100-knot groundspeed on 8.7 GPH. That’s roughly five hours of flight time. My bladder and belly won’t last that long, but it gives me an idea of where to plan my fuel stops. I live in the mid-Atlantic states and east of the Appalachian mountains. Density altitude does come into play when I want to cross the mountains in the summer. This forces me to make gross weight and routing decisions. This is about the only time I wish I had a bigger engine.

Brent Wing

via email

1)]

My family adopted our 1976 bicentennial, red, white and blue Warrior when it was 18 months of age. Now—35 years later—it is still a magical adventure. Seven family members from three generations have earned their private pilot certificates in our family Warrior. The original paint has been touched up and still looks glossy. The interior is 1970s Bahama Blue—a color you can’t get anymore.

Over the years, our Warrior has been modified with panel upgrades, a 180-HP engine, upswept wingtips with landing lights, strobes and flap seals. The mods improved handling and, we think, made it easier to land well.

What do we like about the Warrior? It glides like nobody’s business, and handling is calm and collected at all speeds. The graceful wing has no surprises in the stall and maintains good directional control. With the 180-HP engine, it climbs better and will cruise at 120 knots. Even though it now has Archer performance, the Warrior airframe has advantages. The full-opening cowling allows easy inspection of the engine compartment before each flight and the wheels are an inch smaller, which presents less drag in cruise.

For us, it costs less to own and operate than anything except maybe an LSA. On top of that, the pleasure factor is sensational.

Thomas Reindl

via email

I own a 1976 Warrior with the 160-HP STC mod. I like the airplane because it’s perfect for loading two adults and two children. So far, my Warrior has been inexpensive to operate (for an airplane). Better yet, service parts are readily available.

One of the downsides is the single cabin door, but it is what it is. The Warrior has honest flying characteristics, with no surprises or bad manners.

I like landing it on gusty days because everything smooths out when you are six feet above touchdown due to the low-wing ground effect, plus a nice wide wheel stance.

Everything being equal, it is $10,000 cheaper than a comparable model year Cessna 172, but with similar performance. I feel that the Warrior’s build quality is slightly better than the Cessna.

On average, a 100-knot groundspeed burning 7.5 GPH is typical. You always want more, of course, but that comes with a price. If I move up, it will be to a Piper Arrow, which is essentially the same airframe, but with folding wheels and a constant speed propeller. But, I like my Warrior so much, I might keep it, too.

J. Morgan

via email

I have a 1979 Warrior II (PA28-161) and I love it. It’s easy to fly and when the engine is leaned properly, it’s economical to feed. It’s mechanically simple. During my 15 years of ownership, it has been cheap to maintain.

I own the airplane with a partner, so the costs are shared. We do owner assisted annual inspections and ran the previous Lycoming O-320-D3G engine for 3000 hours before replacing it.

My Warrior is a traveler. In 2012, I flew a grand tour of the United States over the course of a month, which was 6600 NM in 68 flight hours, averaging 7.4 GPH. We flew the Warrior across the Rocky Mountains a few times, to the Grand Canyon and to southern Florida. The airplane has also been to British Columbia.

Domenick Silva

via email